Truancy: Making school the place to be

A good journalist is meant to keep themselves out of the article, but it’s difficult when the topic resonates with your own experience today it’s truancy.

A good journalist is meant to keep themselves out of the article, but it’s difficult when the topic resonates with your own experience today it’s truancy.

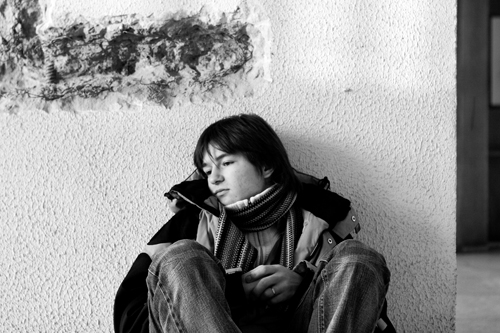

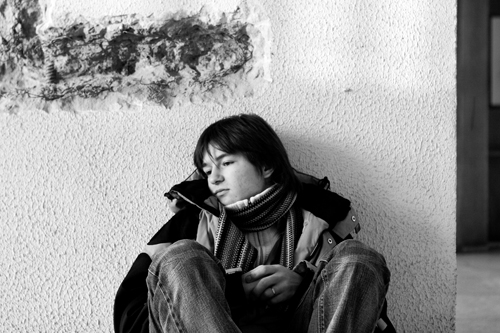

I spent the majority of Year 12 absent from class, either mooching in the common room, or hiving off to a friend’s home for the day.

Able, but incredibly bored, things came to a head when I decided to wag the day the dean had called my mother in to chat about my attendance. Going on report, being signed into every class for an entire term was enough to turn me around and become a model student once again.

All schools, no matter the location or demographics, will have problems with truancy. While some problems can be resolved with a letter home, or a meeting with the parents, for other schools the process of bringing these children back to regular attendance can be incredibly involved.

The legal requirement is that children need to attend school between the ages of six to 16. However, says Auckland truancy officer, Karyl Puklowski, for some children, truant behaviour is already endemic by the time children reach the age of six.

“With some cases we’re looking at three or four generations of children who left school early or didn’t fit in, and there isn’t the parent support to keep these children in school.”

The reasons for truancy are broad and varied.

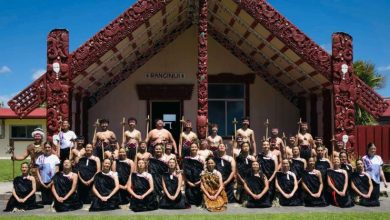

Ted Benton, principal of Glenfield College on Auckland’s North Shore, has worked with his staff to make the school environment more appealing to all students, which increased the attendance rate from 83 per cent to 93 per cent over a twelve month period. They identified that many students were truant due to lack of engagement, and a sense that non-school activities were more fun.

While there are a number of students avoiding school due to other more complex factors, “making school a place our students want to be, where they experience success has done a large part of reducing truancy for us,” says Benton.

As an aside, focusing on the welcoming aspects of school has also led to no tagging or graffiti, another indication that the students are happier at the school.

According to recent figures, schools across New Zealand report an absence rate of around 15 per cent, with truancy rates of eight per cent. Maori and Pacific Islander students often have higher rates of unexplained absenteeism.

Puklowski has also noticed that while the rates of truancy for boys has stayed relatively constant, the numbers of female truants are on the rise. “This corresponds with the rise of females involved in crime, and violence. It’s a reflection of what’s happening in the wider society,” she says.

Discovering patterns of truancy can help find problems before they become insurmountable. School-links provide an early notification software system that helps teachers, parents and truancy officers track a student’s attendance. A text or email is sent out to parents asking where their child is if they do not turn up to school.

Andrew Balfour, managing director of School-links says this can help pick up early truancy. “With approximately 30,000 children away each day through unexplained absenteeism, we can alert the parents as soon as it happens, reminding them to check in with the school.”

The cost of the programme is now fully subsidised by the Ministry of Education for schools meeting certain criteria, covering set up and annual running costs.

While it’s often the school that first identifies that truancy is a problem (normally sending home a letter, followed by a meeting with the student’s family), the legal responsibility is with the parent to ensure the child attends.

Prosecuting families for truancy is rare in New Zealand, and a truant officer has to find other strategies to bring students back to school. Once a child has reached high school, some of the responsibility does fall to them to attend, though it’s still the family that holds the legal responsibility.

“It’s our job to handle complex relationships. We act as an advocate for the student. Often a school has felt they’ve tried everything so it’s really providing a different perspective, finding a solution that perhaps hasn’t been tried,” says Puklowski

It’s an involved process, especially when the truant behaviours are embedded into the family dynamics. “We’ve recently worked with one family of six children. We had to come in with the first five and bring them back into school. The sixth child is attending school without our help. That’s progress.”

Benton says it always comes down to relationships. “We work hard to build positive relationships between the teachers and the students. We have a restorative approach to behaviour management. Our students see this school as a positive place to be.

If they know there are people at school who really care about them, where they know they will be treated with fairness and respect, they will be more likely to turn up. They’ll just want to be at school.”

And as for me, the journalist who brought herself into the story? Going on report broke the pattern, and I was an almost model student during Year 13 – at least in terms of attendance.