Children’s beliefs affect maths performance, researcher says

A general perception that New Zealand school children are not doing as well as they should in maths may not be entirely correct, a University of Canterbury researcher has found.

A general perception that New Zealand school children are not doing as well as they should in maths may not be entirely correct, a University of Canterbury researcher has found.

University PhD education student Cathy Solomon says public perception suggests New Zealand school students are not handling maths well. Many children and adults seem to be giving up on mathematics all together, she says.

Ms Solomon surveyed 71 teachers and 823 children and she is not convinced that New Zealand students are doing that badly at maths. “However, we could do better. Part of the problems with international maths comparisons is that skills that are easy to test and compare are used rather those that are more complex and creative.

“Rather than how good we are, I am interested in whether or not we believe we are capable of doing well at maths. Those who believe they are capable are more likely to work hard, not give up when things get difficult, remain interested in the subject and do better in the long run.

“We know that those with maths beliefs do better. Beliefs affect children’s and teachers’ attitudes and performance. Many people are quite happy to say they can’t do maths so why bother to try. They disengage completely from the subject.

“Although more young people are remaining at school until the end of years 12 and 13, proportionately few go on to study maths beyond the required number of NCEA credits or at universities for courses such as for engineering or psychology.”

In her study supervised by Dr John Hannah and Dr Jane McChesney, Solomon looked at children’s and teachers’ beliefs about what maths is and how it works. She also examined beliefs about which children could or could not do maths.

A problem associated with studying beliefs is the lack of consensus about how to access and analyse them. “The study exposed a rich and complex landscape of mathematics beliefs that were influenced by how mathematics is taught and learnt at school as well as by participants’ ethnicities, gender, socioeconomic status and achievement levels.

“Children and teachers positioned certain people as good at mathematics or not good at mathematics. They referred to the children in the top groups and Asian students as good at maths but did not refer to Māori and Pasifika as weak at it.

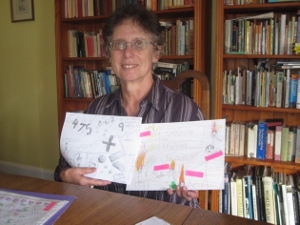

“Most exciting results came for the drawings, a technique I developed in response to children not wanting to, and some not being able to, write about their beliefs. They used metaphors such as maths as problem solving, maths as useful, maths as numbers, maths as life and maths as brain burn inducing. “Teachers may be able to help children develop the sorts of beliefs that may make them more successful maths students,” Ms Solomon says.