Re-focusing teaching practice to being responsive, engaging and inclusive has had a huge impact on student achievement at Napier’s William Colenso College. In 2011, NCEA level two Maori achievement was at 48.6 per cent but by 2016, it was at 76.5. Principal Daniel Murfitt explains how…

William Colenso College celebrates being co-winner of the Prime Minister’s Education Excellence Award for Leadership. This award, Atakura, alongside being finalists in the Excellence Award in teaching and Learning, Atatū, and Excellence in Governing Award, Awatea, recognises an outstanding school culture focused on accelerating achievement and reducing disparity. This has been achieved through focus on building powerful relationships between students, teachers and whānau, shared accountability and a responsive curriculum which offers many pathways to success.

A strong overarching feature of the school is the focus on building and fostering positive relationships with the whole school community. Many initiatives have contributed to the strong culture of wellbeing; restorative practice, culturally responsive and relational pedagogy, the vertical form structure for years ten to 13, CACTUS, the development of Te Whānau Ora as a learning and behaviour centre, PB4L, and the Manaakitanga group (Deans). Through the PB4L programme the school has also embedded the school values of manaakitanga (care and respect), whānaungatanga (belonging) and hirangatanaga (striving for excellence).

“I started William Colenso College in year eight and my journey at school has been amazing. There are so many opportunities at William Colenso. One of the greatest things is that every teacher is supportive and willing to help you succeed in school and in life. Next year I am hoping I will be accepted in EIT or Waikato University to become an occupational therapist or a social worker,” says head girl, Tala Utumapu.

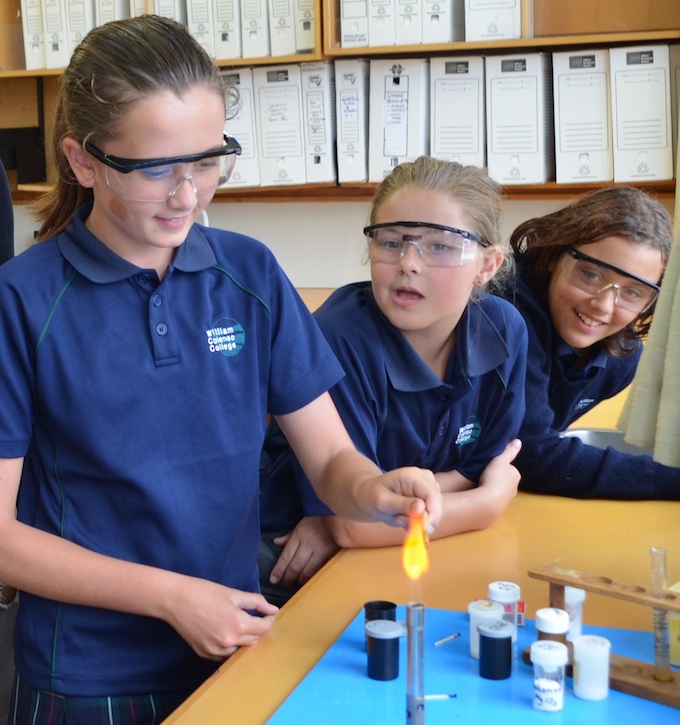

William Colenso College is at the forefront of teaching and learning, utilising best practice, research and collaboration within to push back the barriers for our learners and provide an equitable environment for learning. Our teachers are using authentic learning experiences for our learners, and providing evidenced based programmes, which supports a positive school and community environment.

Teacher collaboration is a keystone to the improved achievement in our learners. There are regular teacher meetings about the learning of groups of students and how the teachers are developing new strategies, knowledge and learning to use in the classroom. These strategies and practices are now embedded in the school culture and practice.

What we set out to achieve

Most of our learners fall in the priority category as set by the government. They need and deserve to be at a school with excellent teachers and leaders who have their well-being and achievement at the centre of all that happens in the school. They need leaders and teachers who advocate for them and challenge deficit thinking; who work collaboratively with learners, other staff and the community; who use evidence to inform their practice and are constantly reviewing processes and structures in the school. All these actions allow the school to be responsive which enables the development of strategies to address the need for social justice and equity for our learners.

The school has delivered on its vision to transform school culture to lift Māori engagement, achievement and outcomes at the school, using a distributed leadership model to improve social justice and effect equity for all the students. Change had to be initiated so that all staff could participate in an equitable bicultural school environment.

We learned that when there is relational trust in the school between the leaders and the whole school community then there is a true model of tuakana/teina, where roles can easily change depending on the context, experience, and knowledge of those involved. This creates leadership in others which is mana enhancing.

This collaboration is also evident in the senior leadership team. Phil Robertshaw, SLT member says, “It’s very even and it’s not as though Daniel as principal is the boss and telling us what to do, it’s very much co-constructed. Everyone contributes relatively equally and easily.”

Leaders in schools need to be leaders of learning where they take part authentically in professional learning and collaboration with teachers. It gives those leaders a deeper understanding and knowledge of what is happening in the classroom for individual teachers, what skills those teachers have and where support is needed. Leaders can then use their expertise to coach and advise teacher on their practice and allow the teachers to develop their leadership, and teaching and learning relationships with the students in their class.

We know that we have to be responsive to the changing needs and requirements of our modern learners. We often have to be prepared to disrupt the status quo to allow for a more equitable and innovative school. This means it is sometimes uncomfortable, but if we can support each other and collaborate through this change then the benefits to the outcomes for Māori (and all) will be accelerated – as is evident in our achievement data and student well-being voice.

Teacher collaboration is a keystone to the improved achievement in our learners. There are regular teacher meetings about the learning of groups of students and how the teachers are developing new strategies, knowledge and learning to use in the classroom. These strategies and practices are now embedded in the school culture and practice.

“You are agentic, responsive, there is collaboration, you act with expertise, and you have shared expertise which is obviously based on relevant evidence.” Margaret Egan of Waikato University.

Our changes in practice include:

- The development of teacher agency and removal of deficit theorising

- The development of a culturally responsive pedagogy

- A move from traditional interactions in the classroom to more discursive interactions

- Curriculum design and delivery that was responsive, engaging and inclusive

- The development of teacher understanding of restorative principles and techniques to manage conflict

- Teacher knowledge of Te Ao Māori (reo and tikanga)

- Teachers needed to own the changes – be part of the improvement and not have it ‘done’ to them.

The BOT has seen the need for sharper disaggregated data for Māori and non-Māori, and asks questions about who is achieving and in particular how named Māori students are achieving.

“We respond to what we see in the evidence and that coherently aligns with supporting Māori students,” says deputy principal Fiona Craven.

Meetings also had to be aligned to the new culture being developed within the school. They had to be meaningful and at times when the data was available. Data also had to be collected appropriately and stored in logical places. Everyone had to understand his or her responsibility in this data collection. SLT developed data collection plans which are reviewed and updated every year.

Ms Craven says, “Different data has different cycles so you have NCEA data at the beginning of the year for the previous year, but you also have interim data throughout the year from about April.”

Development of restorative practices

The deliberate focus on relationship building allowed for the cultural change that needed to happen in the school. Te Kotahitanga supported this change in culture, but the implementation and development of restorative practices also had a major impact. Restorative practices were used in the school previously but only for high-end incidents whereas they are now fully imbedded into the culture and across all school systems.

“You can’t have a punitive approach with a relationship based pedagogy so a defining moment was probably our decision to go down that pathway at an accelerated rate,” says Mr Murfitt.

Financial leadership

Since 2008, the college finances have progressively improved. This has been a result of ongoing review by the audit committee (set up in 2009 to review finances). The audit committee was set up to develop a leadership group to collect and analyse finances, and in particular, the impact of fluctuating income of the school. Programmes, staffing and resourcing are put under the microscope to assess the impact of the resources allocated to each area. As a result, resources have been removed from areas which have a lesser impact on student engagement and achievement, and increased in areas which have had a greater impact, for example, restorative facilitator.

In 2013, we were finalists in the Hawkes Bay Business Awards. This provided us with both profile and recognition for the work we have put in during the last few years to ensure we are financial stable and delivering a quality educational product for both domestic and international students.

What difference did the changes make?

We have a collaborative collegial school where Māori achievement continues to improve. We have a distributed leadership model where everyone is a leader. Senior leaders have moved from individuals with set roles in the school to a collective who collaborate effectively at all times.

The pedagogical change in the classroom is evidenced by sustained improvement in student achievement at NCEA, and through shifts in teacher practice evident in Rongohia Te Hau (annual evidence collect by student survey, teacher survey, whānau survey and teacher observation).

This pedagogical and leadership change has been acknowledged internationally with Mr Murfitt attending the WISE Awards in Doha, Qatar, and by being invited to present to a range of government and indigenous groups in Saskatchewan, Canada.

We are constantly reviewing our practice and are aware that feedback from the 2016 survey is that as senior leaders, we need to be aware of protecting the time we have for teaching and learning. Teachers would like us to reduce additional demands and interruptions.

A critical measure of success is in our student achievement from 2009 to 2016.

William Colenso College now has strong structures and institutions in place that all align with the strategic direction of improving outcomes for Māori. Our inquiry cycles at the three levels, individual, department and school wide provide us with evidence to continue with our pathway and self-review. They allow us to build on our practice and continually improve the way we do things. Through our strong self-review process we are constantly looking at improvement – we will never get to the ‘end.’

We give our students an environment where it is comfortable to be Māori. They do not need to change when they walk through the school gates.

Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi, engari he toa takitini.

My strength is not mine alone, but comes from the many. My successes are not due to my own efforts but are the result of input from many others.

William Colenso College is a co-educational high school in Napier. Of the 420 students, 64 per cent identify as Maori, 16 per cent as New Zealand European, and ten per cent as Pasifika.