A guide for teachers: what to do if a teenager watches violent footage

The world is reeling in the aftermath of the horrific shootings in Christchurch.

The attack has also raised a number of side issues, including the ethics of broadcasting the live stream of the attack, which was later shared on other platforms.

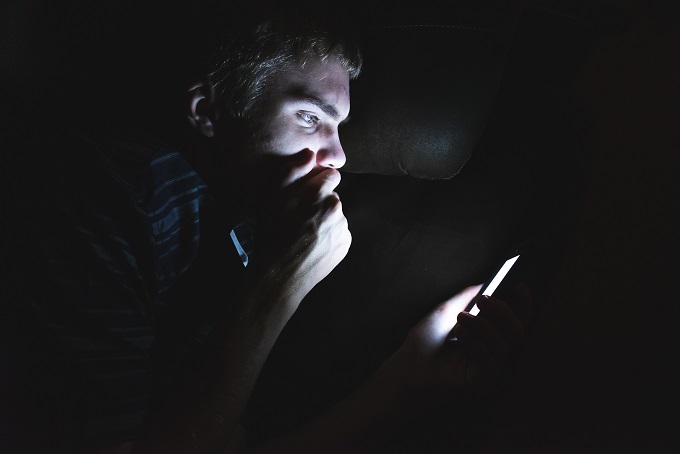

As social media is fast becoming the favoured news source among young people, concerns have been raised about the potential impact such footage may have on those exposed to it.

YouTube, Facebook and Twitter so far failing to stop the proliferation of the Christchurch shooting video. It’s spreading, being re-posted, re-filmed. None of the tools they’ve implemented move fast enough. (Many media outlets also failing dismally to make the right choice.)

— Ariel Bogle (@arielbogle) 15 March 2019

Adolescents are particularly affected by violent imagery. As their brains are still developing, they may have trouble processing the information. This basically means the bits of information teens will pay attention to, what they highlight in their memory, and how they organise, conceptualise or contextualise information is still a work in progress. In adults, this is more or less set.

The use of social media as conduits for extreme violence is a relatively new issue and a fast moving beast. So research has struggled to keep up with potential emerging impacts.

But there are some things we do know about the impact of violent imagery on the adolescent brain, and ways in which adults can help teenagers process such information.

Violence and the

developing brain

Concerns regarding the impact of violent imagery on the developing brain are nothing new. They were first raised after images of the second world war appeared in some of the first television broadcasts from the late 40s. By the early 70s, the US Surgeon General acknowledged the potential for harm of such footage on younger members of the community.

Fast forward to today and a raft of different research methods continue to demonstrate links between exposure to media violence and increased aggression or fear in adolescents. The primary concern for older male adolescents appears to centre around its impact on aggressive tendencies. But younger adolescents may also exhibit heightened fear responses.

The #Christchurch shooter clearly wanted that horrific footage shared. Don’t do it. Don’t watch it. It is a nightmare. Hearts are with New Zealand & muslim friends. What a horrible day. Numb. @Twitter take down his account ASAP.

— Sophie McNeill (@Sophiemcneill) 15 March 2019

A couple of primary issues appear to be at play. Exposure to violence can lead to desensitisation, which contributes to later acts of violence in adolescence. The psychological mechanism by which this occurs suggests desensitisation from habitual media violence reduces fear and promotes aggression enhancing thoughts. This increases the likelihood of proactively committing an aggressive act.

Peer norms remain a strong benchmark for most teenage behaviour, and these too appear to influence aggression (either increasing or decreasing), suggesting a role for social context.

It may then be fair to speculate that peers sharing violent content via social media could provide a perfect storm of desensitisation and tacit peer approval of, or at the very least encouraging interest in, acts of extreme violence.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has signalled their concerns regarding the potential harmful impact of media violence on teens, and suggested parents and schools need to be vigilant in responding to the influence of social media.

And a number of studies have recommended limiting exposure to social media, or monitoring its use, as well more action by social media sites to prevent streaming of violence. How such recommendations can be practically achieved with today’s ubiquitous use of social media is a trickier question.

So what can parents

and teachers actually do?

Research into possible ways of ameliorating the effect of media violence in influencing adolescent aggression or fear has arrived at some helpful pointers for both parents and teachers:

discuss what you are seeing on television (or Facebook) with the teenager. Remaining silent during the broadcasting of violent imagery can be perceived by your teen as tacit endorsement of the depicted acts

engage your teenager with questions and improve their empathy by looking at the impact of the violence from several points of view. For instance, what about both the victim’s and perpetrator’s family – how must they be feeling now? This appears to be a more effective approach with teenagers and young adults than simply stating your own point of view

parents and schools can take an active role in directly teaching adolescents about media manipulation methods and falsehoods spread to serve a particular agenda. This includes how to spot fake news, hoaxes and propaganda

help the teenager develop critical thinking and a healthy level of cynicism. This can be done by encouraging them to take a step back and think about the motivations of those who report or broadcast especially violent or confronting imagery.

If you notice a substantial change in a teenager’s behaviour following a highly publicised violent act – such as being frightened to take public transport, checking locks at night, keeping weaponry on them or nearby, or suddenly more being aggressive and/or anxious in general – it may be time to seek help from your school counsellor or GP.![]()