Dyslexia and beyond: Understanding different learning styles

Brains are fascinating, mysterious things but perhaps the most interesting feature of the human brain is ‘neurodiversity’.

The term was invented in 1988 by an Australian academic called Judy Singer but ‘neurodiversity’ as cultural notion has only crept into the mainstream this decade. Essentially, it predicates the idea that in any human population there will be a natural variation in neurological difference. In other words, people think in different ways so why would everyone learn the same way?

This article originally appeared in our Term 1 magazine. Click here to read the full version!

Teachers know that children have different learning styles but, according to estimations provided by the Dyslexia Foundation, one-in-ten New Zealanders have dyslexia, including 70,000 schoolchildren. For those children with dyslexia, and others with equally specific learning disabilities like dysgraphia, dyspraxia, ADHD, and the less commonly known Irlen Syndrome, there are commonly held misconceptions to debunk and a heap of resources and support for schools to utilise in 2019.

Dyslexia is, first and foremost, a different way of thinking. With that comes a variety of different abilities and challenges but it is by no means an intellectual disability. Dyslexia has no impact on intelligence whatsoever, it simply changes an individual’s learning preference. Students who have not been empowered to learn in the way they need to learn will struggle in the classroom and, eventually, feelings of low self esteem can set in. Reports show that it is unfortunately quite common for children with dyslexia to believe that they are less intelligent than their peers but research proves that this not the case.

Dyslexia makes decoding words on a page more difficult. It makes processing certain things tricky and this makes activities like reading and spelling very challenging for students with a language-based learning disability. A child with dyslexia may also struggle to learn how to tell time, follow directions, read or spell but they can often be gifted in other areas like conceptual thinking, creative problem solving and spotting patterns. In fact, there are plenty of gifted and well known individuals with dyslexia who have earned their success in a wide range of industries. Some examples to share with students include: Steve Jobs, Sir Richard Branson, Steven Spielberg, Kiera Knightley, Cher, and Harry Potter himself, Daniel Radcliffe has a different learning disability called dyspraxia, which affects motor skills.

According to the International Dyslexia Association, 85 percent of children diagnosed with a learning disability have one that primarily impacts reading and language processing. For many of these children, the first year of school will be the first time their language processing difficulties are obvious as it’s the first time they are learning to read amongst same-age peers. So it’s vital that schools are quick to identify, screen, assess and support these children. Yet, the Ministry of Education has been relatively vague about how schools can do this, until more recently. In fact, it wasn’t until 2007 that the New Zealand Government officially recognised dyslexia at all.

Now, the MoE has an online ‘Guide to Dyslexia and learning’, which has simulation videos, pages of information for teachers and PDF downloads for schools. These can all be found at: www.inclusive.tki.org.nz. The MoE insists: “Once identified, it is important that dyslexia is not regarded as a label, but rather as a call for action. Modifying the learning environment will benefit all students.”

This presents two asks for teachers, then: first, how to identify these students and second, how to modify the learning environment.

Identifying students with signs of dyslexia (and what to do next)

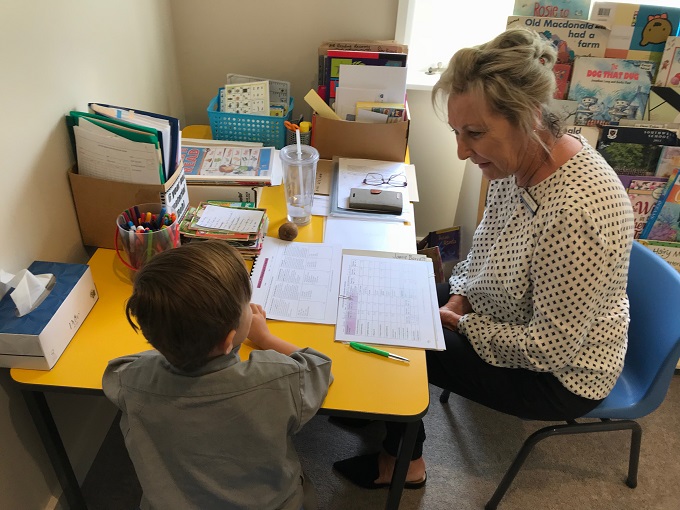

The MoE has a detailed list of assessment guidelines for schools and teachers so that they can identify children with signs of a learning disability at the youngest possible age, five in most cases. They should then put programmes in place to support any children presenting with specific needs, then monitor and reassess later on to determine whether they still show signs of dyslexia or another learning difficulty.

One example of such assessment is an extended version of the Six Year Net, or observation survey, which should be used to assess students between ages five and seven, the MoE advises. Here, “some of the most useful information can be obtained from a careful analysis of the student’s strengths and needs. In most cases, this should lead to well-informed teaching decisions designed to make learning of new information as easy as possible.”

While the Ministry encourages teachers and principals to be trained in and research dyslexia, it should be noted that these in-school assessments are not diagnostic. They operate more like a screening process so that by the time a child is six or seven they can be referred to a specialist for an accurate cognitive and educational diagnostic assessment.

One reason it is critical that students who have persistent learning difficulties in certain areas are referred to a specialist, is that there are multiple and lesser known learning disabilities that the student could have. Even a school that has an inclusive learning environment and teachers that are well-versed in dyslexia support may not be aware of alternative diagnoses like Irlen Syndrome. A child who is assumed to have dyslexia, for instance, without a proper diagnosis may face further challenges in their learning and behaviour as they grow up.

Irlen Syndrome is a visual processing issue that affects about one-tenth of the population. Incidence studies indicate that 46 percent of people who have been identified with reading problems, dyslexia, attention deficit disorder, or learning difficulties suffer from Irlen Syndrome. For these people, words on the page can look like they are shaking, waving, blurry, shuffling, or like there is a ripple effect over the page. Students may suffer from headaches or eye strain while reading and tend to have trouble following lines of text.

Modifying the learning environment for students with language processing difficulties

There are specific classroom techniques that can be used to help students with Irlen Syndrome, such as dimming computer and whiteboard screens, turning off lights, providing more frequent reading breaks or increasing font size on worksheets. However, the best solution is for the student to meet with an Irlen diagnostician who can supply them with glasses that have specially tinted lenses to filter out the particular wavelengths of light that cause their symptoms.

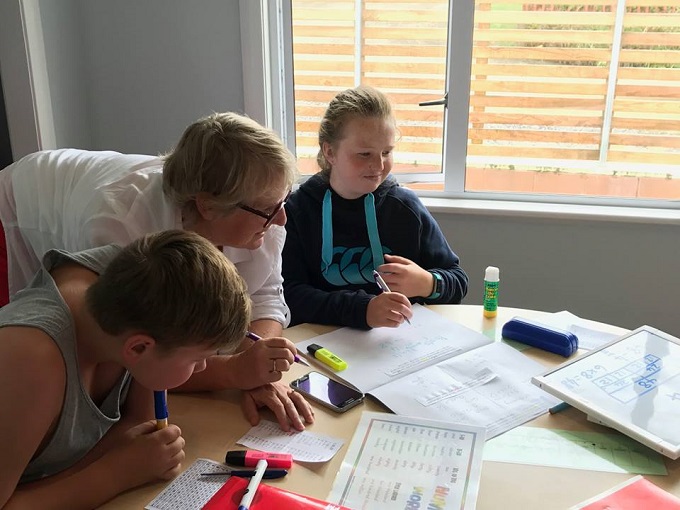

One of the major things schools can do to support students with dyslexia, is to retest written assessment orally so that students are able to display their knowledge most effectively. Flipped learning and various visual online programs are also recommended as people with dyslexia are visual learners and the online component allows them to do so independently.

It’s vital that schools take the time to upskill their teachers as much as possible about learning disabilities like dyslexia and Irlen Syndrome because, as the Ministry notes: “Approaches that are useful for students with dyslexia are often valuable for everyone.”