Changing minds about mathematics

We are living in what Associate Professor of Mathematics, Frank Farris dubs a “golden age of mathematical visualisation”.

Arguably, the learning and application of mathematics has never been more creative, with the gamut of STEAM projects, computer and digital technology available for students to explore what mathematics can do. Yet, according to the latest PISA results, the average mathematics score of New Zealand students declined between 2003 and 2015 from 523 to 495 points. The proportion of students that “can complete only relatively basic mathematics tasks and whose lack of skills is a barrier to learning” rose from 15 percent to 22 percent.

Read the Term 2 issue of School News here.

So how can schools put together a programme that combines real-world innovation and creativity with emphasis on mastering foundational maths skills? To find out more, School News spoke with some of the minds behind maths programmes taught around the country.

Symphony Math founder and CEO, Paul Schwarz discussed the latest maths trend, and the benefits of more controversial teaching techniques.

The most important trend in recent years is the effort to empower students with solid mathematical strategies and the freedom to experiment and learn from mistakes. As math educators and learners, we need to replace the idea of mathematics as tedious question-answer routines and come to appreciate the beauty and richness of the discipline.

In terms of controversial learning incentives, such as financial rewards for completing maths homework; if mathematics education is limited to an endless routine of procedures and recall, then desperate measures may be introduced to try to encourage attention and growth. Of course, this sort of motivation cannot succeed, and avoids the real issue: mathematics learning needs to engage students intrinsically.

Each learner has a unique path to mastery. The right programme allows students to work at their own pace, and provides teachers with insights into students’ strengths and weaknesses that help guide their decision-making. Teachers need access to group-level and individual student reporting so that they can ensure consistent use and real-time access to information.

Schools need to consider their school’s core motives when choosing a mathematics programme. Which tools will best support learning that will benefit students’ expanding view of the connections between new material and mastered material? For example, teaching young students the idea of parts and wholes is critical, and of course the foundation of all basic operations. Students need many opportunities to master this concept, and then apply it in many different contexts, such as measurement and data analysis.

In my opinion, schools are best served by concentrating on helping students master foundational math skills, and then transfer those skills to as many mathematics environments as possible.

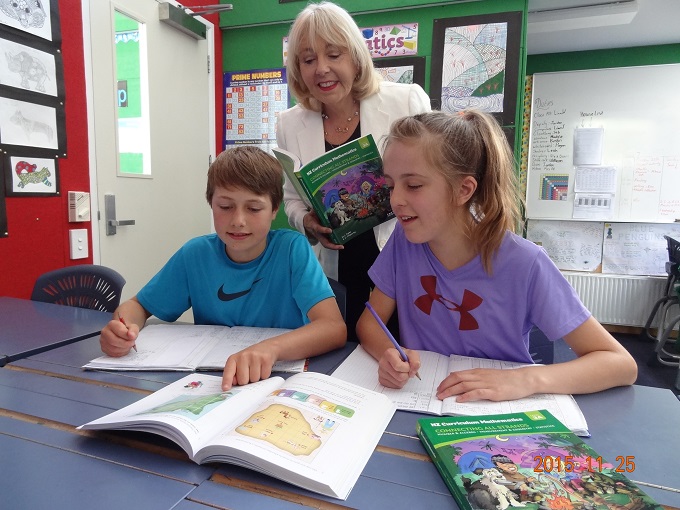

Caxton Educational curriculum facilitator Joel Bradley, and teaching consultant of Caxton Educational’s Connecting All Strands series Jenny Holland,. spoke to School News about changes in mathematics pedagogy and how classrooms should adapt.

I see less emphasis on maths memorisation of facts. The pendulum seems to have swung to more emphasis on problem-solving, collaborative group work, and culturally responsive pedagogy. It has become more student centred and maths problems have become more open-ended with an emphasis on authentic and relevant contexts, which has allowed students to bring their own knowledge and understanding to the question and work out solutions in different ways.

There is a greater expectation among primary teachers that they will be able to explain how they came to a solution and students can share this in a greater variety of ways; perhaps an equation, but also with diagrams, number lines and even manipulatives. Maths and problem solving is done more frequently with a partner or in small groups. I think teachers still recognise the importance of having fluent recall of basic facts but are less inclined to include ‘drills’ that prioritise speed as an indication of maths ability. Teachers also have an appreciation that students need to be able to fluently recall and apply other mathematical knowledge, such as place value and fractions, to be competent mathematicians. The DMIC approach is gaining ground. Any programme that allows children to think deeply about and approach problems from different angles is a winner in my book.

The gamification of learning is a big trend, and I can’t see why this trend shouldn’t continue. Games have been shown to improve engagement; however, it is most dependent on the quality of the ‘fun’ activity or ‘game’, whether online or offline. The ability of the teacher to identify the potential for learning within the ‘play’ and to support the students so that they take advantage of this potential is crucial.

A programme that offers rich tasks with multilevel groupings allows students of all abilities to engage and add to the conversation. Even the shy, non-maths-oriented students shine in this context. Scaffolding and progressions that support student success are also important because students who feel they are successful at mathematics also have the most positive attitude to this curriculum area. Problems that incorporate number into strands or make connections between strands is a good way to consolidate understanding and improve engagement and relevance.