This is the second of two essays exploring key theories – cognitive load theory and constructivism – underlying teaching methods used today.

Constructivism is an educational philosophy that deems experience as the best way to acquire knowledge.

We truly understand something – according to a constructivist – when we filter it through our senses and interactions. We can only understand the idea of “blue” if we have vision (and if we aren’t colour blind).

Constructivism is an education philosophy, not a learning method. So while it encourages students to take more ownership of their own learning, it doesn’t specify how that should be done. It is still being adapted to teaching practice.

The philosophy underpins the inquiry-based method of teaching where the teacher facilitates a learning environment in which students discover answers for themselves.

How developmental psychology shapes learning

One of the earliest proponents of constructivism was Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, whose work centred around children’s cognitive development.

Piaget’s theories (popularised in the 1960s) on the developmental stages of childhood are still used in contemporary psychology. He observed that children’s interactions with the world and their sense of self corresponded to certain ages.

For instance, through sensations from birth, a child has basic interactions with the world; from two years old, they use language and play; they use logical reasoning from age seven, and abstract reasoning from age eleven.

Before Piaget, there had been little specific analyses on the developmental psychology of humans. We understood that humans became more cognitively sophisticated as they aged, but not exactly how this occurred.

Piaget’s theory was further developed by his contemporary, Lev Vygotsky (1925-1934), who saw all tasks as fitting into:

tasks we can do on our own

tasks we can do with guidance

tasks we can’t do at all.

There’s not a lot of meaningful learning to be made in the first category. If we know how to do something, we don’t gain too much from doing it again.

Similarly, there’s not much to be gained from the third category. You could throw a five year old into a calculus class run by the most brilliant teacher in the world but there just isn’t enough prior understanding and cognitive development for the child to learn anything.

Most of our learning occurs in category two. We’ve got enough prior knowledge to make sense of the topic or task, but not quite enough to fully comprehend it. In developmental psychology, this idea is known as the zone of proximal development – the place between our understanding and our ignorance.

Using the zone for learning

Imagine asking ten-year-old students to go about adding every number from 1 to 100 (1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 and onwards). They could theoretically do this by brute force addition which will likely bore and frustrate them.

A constructivist inspired teacher might instead ask: “is there a faster way of doing it?” and “is there a pattern of numbers?”

With a bit of help, some students might see that every number pairs with a corresponding number to add to 101 (1 + 100, 2 + 99, 3 + 98). They end up with 50 pairs of 101, for a much easier, faster sum of 50 x 101.

The pattern and easy multiplication might not have come intuitively (or even at all) to most students. But facilitation by the teacher pushes their existing knowledge into a meaningful learning experience – using a completely mundane problem. It then becomes a process of discovery rather than monotonous addition.

Medical students began using constructivist pedagogies in US and Australian universities in the 1960s. Instead of teachers showing students exactly how to do something and having them copy it (known as explicit instruction), tutors prompted students to form hypotheses and directed them to critique one another.

Constructivist pedagogy is now a common basis for teaching across the world. It is used across subjects, from maths and science to humanities, but with a variety of approaches.

The importance of group works

Learning methods based on constructivism primarily use group work. The emphasis is on students building their understanding of a topic or issue collaboratively.

Imagine a science class exploring gravity. The question of the day is: do objects drop at different speeds? The teacher could facilitate this activity by asking:

“what could we drop?”

“what do you think will happen if we drop these two objects at the same time?”

“how could we measure this?”

Then, the teacher would give students the chance to conduct this experiment themselves. By doing this, teachers allow students to build on their individual strengths as they discover a concept and work at their own pace.

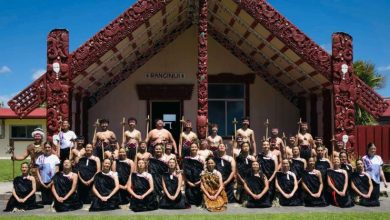

Experiments in science class, excursions to cultural landmarks in history class, acting out Shakespeare in English – these are all examples of constructivist learning activities.

What’s the evidence?

Constructivist principles naturally align with what we expect of teachers. For instance, teacher professional standards require them to build rapport with students to manage behaviour, and expert teachers tailor lessons to students’ specific cultural, social and even individual needs.

Explicit instruction is still appropriate in many instances – but the basic teaching standard includes a recognition of students’ unique circumstances and capabilities.

Taking the constructivist approach means students can become more engaged and responsible for their own learning. Research since the 1980s shows it encourages creativity.

Constructivism can be seen as merely a descriptive theory, providing no directly useful teaching strategies. There are simply too many learning contexts (cultures, ages, subjects, technologies) for constructivism to be directly applicable, some might say.

And it’s true constructivism is a challenge. It requires creative educational design and lesson planning. The teacher needs to have an exceptional knowledge of the subject area, making constructivist approaches much harder for primary school teachers who have broader general knowledge.

Teacher-directed learning (the explicit teaching of content) has been used for a lot longer, and it’s shown to be very effective for students with learning disabilities.

A major challenge for constructivism is the current outcomes-focused approach to learning. Adhering to a curricular requirement for assessment at certain times (such as end-of-term tests) takes the focus away from student-centred learning and towards test preparation.

Explicit instruction is more directly useful for teaching to the test, which can be an unfortunate reality in many educational contexts.

An an education philosophy, constructivism has a lot of potential. But getting teachers to contextualise and personalise lessons when there are standardised tests, playground duty, health and safety drills, and their personal lives, is a big ask.