Engaging junior learners and whānau from home

Ko koe ki tēna, ko āhau, ki tēnei kiwai o te kete. You take that handle of the kete and I’ll take this one.

A joint blog by Anne Kenneally and Rachel McNamara

Teaching and learning is all a bit of a puzzle right now; not a simple child’s one with only one place where each piece fits, but more like a Wasgij puzzles where we can’t see the finished picture and are unsure how long it will take to complete.

Thankfully we do have many clues:

- We can draw on our understanding of how our junior primary ākonga learn, our knowledge of effective teaching practices, and what has worked well in the past.

- We are learning through being in lockdown ourselves what support we value as parents and for our tamariki.

- Our networks of friends, whānau and colleagues are sharing stories.

- The internet is bustling with recommendations.

We also have a challenge. How do we sift through this multitude of clues to ensure we can contribute to the puzzle unique to our learning community here in Aotearoa?

Finding a way forward

We would like to share with you a philosophy or practice known as Āta: An Indigenous Knowledge Based Pedagogical Approach to Teaching (Forsyth & Kung, 2017), which focuses on growing respectful relationships. It is a teaching philosophy grounded in Te Ao Māori.

As you journey through ‘learning from home’, we would like to share some observations aligned to three of Āta’s guidelines:

- Āta-whakarongo – to listen with reflective deliberation

- Āta-noho – giving quality time, to be with people and their issues.

- Āta whakaaro – to think with deliberation, considering possibilities

PUZZLE PIECE 1: Focusing and reflection on the relationship between whānau, ākonga, and kaiako

RACHEL: Andrew, a 6-year-old, was in my class a few years ago. He had Cystic Fibrosis. For periods of time, due to the bugs going about the school, Andrew and his whānau, would self isolate, to ensure his health wasn’t compromised. When this happened I would put together a pack of things for him to have at home. It would include books he could read independently, books Mum could read to him, activities I thought might interest him, and topic related work. I would check in with Mum and Andrew regularly by phone and take around new packs as needed.

I look back now and reflect on how I would do things differently in light of new technologies available now. Really, the only difference is that Andrew’s beloved PS4 would connect to the internet, as would Mum’s cell phone. I can imagine, after discussion with Andrew and his mum, we would have been collaborating online.

I look back now and reflect on how I would do things differently in light of new technologies available now. Really, the only difference is that Andrew’s beloved PS4 would connect to the internet, as would Mum’s cell phone. I can imagine, after discussion with Andrew and his mum, we would have been collaborating online.

The word I want to draw your attention to is “discussion” not the internet.

Making multiple, ongoing opportunities to connect and listen to our whānau and ākonga is what will create the weave that supports ako. This is the puzzle piece.

As educators, there is a pressing need to “get something out” to whānau and ākonga. But maybe think of the first offerings, like the nibbles before a meal. Let’s koha something light to help us all settle in. And let whānau know that is what we are doing.

Now as we prepare for the ongoing “main meal” of teaching and learning together, let’s begin with Āta-whakarongo – making time and opportunity to listen with reflective deliberation.

Here are some questions we might ask whānau and ākonga to help us understand what’s on top and how we can usefully support collaboration, taking the handles of the kete together:

- I’d like to be able to touch base with you and your child on a regular basis. What are the best ways for us to connect: email, txt, phone, skype, social media?

- We are keen for tamariki to stay connected with their friends and classmates. How is your tamariki staying connected currently? What might work for you?

- We want to be able to continue to support your child in their learning, but we want it to be manageable for you. We are keen for this to be fun and supportive, not stressful. What kinds of learning activities do you think would work best in your household?

- Some learning activities may need the support of an adult. Is there anyone in your household who will be able to listen to your child read or help with a learning activity?

As we make time for Āta-whakarongo – time and opportunity to listen with reflective deliberation – we learn about what is important for whānau and their tamariki at this time. We then can allow the preferences, needs and sensitivities of our whānau and ākonga to guide our decision making about what teaching practices and learning activities might be useful and of value. This gives us a puzzle piece, unique to our community.

PUZZLE PIECE 2: Learning from the stories of others

ANNE: Āta-noho – giving quality time, to be with people and their issues is our common thread here. The explosion of learning and innovation is remarkable and deeply heartening.

My first learning is marvelling at the way leaders and teachers are prioritising connection and the value this has for both whānau and ākonga.

My first learning is marvelling at the way leaders and teachers are prioritising connection and the value this has for both whānau and ākonga.

Here’s an example from parent Eloise Sime:

“A big shout out to the principal of Grant’s Braes School in Dunedin, Gareth Taylor. He’s organised a Zoom meeting to read stories to the kids at 9am on weekdays.It’s such a special way for him to connect with the kids and they love it. 85 families joined the read aloud Zoom on the first morning.”

For our very junior ākonga, technology offers opportunities for continuity of reading aloud. If you are using the Google Suite for education you may want to explore reading online using voice typing. Some kaiako are setting up Google Slides to allow whānau to drop in video of learners reading aloud, creating a resource for ākonga to not only share their reading but connect with classmates, hearing each other’s voices. This could also be extended to allow ākonga and whānau to share oral histories.

My second learning comes from watching our ākonga learning with whānau in their bubbles, and it is inspired by colleagues and communities in the Chatham and Pitt islands.

Already the schools I work alongside are brimming with stories of whānau; making kai, setting building challenges, indoor and outdoor treasure hunts, storytelling, viewing and explaining whānau photos and gardening with their tamariki.

Now is the time for Āta-noho, quality time to be with our people and their issues. How we connect with ākonga now will be more important than what we ‘teach’ (taking the handle of the kete together). Palmer (2007) affirms that “the connections made by good teachers are held not in methods but in their hearts – meaning heart in its ancient sense, as the place where intellect and emotion and spirit converge in this human self.” (11). We are seeing ‘heart’ in action in current sharing. This is the second puzzle piece.

PUZZLE PIECE 3: Recognising, valuing, and supporting the awesome capabilities of our junior ākonga

RACHEL: Āta whakaaro – to think with deliberation, considering possibilities is the focus of our last puzzle piece

Tamariki in the junior years are quick to play and often soak up new learning quickly; they will take risks with tools, and are often keen to show whānau (and possibly you) how to do new things.

As we design learning activities for our learning from home curriculum, we want to ensure that we create opportunities where ākonga can stretch out and expand their capabilities. Let’s not limit opportunities for learning.

For example, a school we are working with is focusing on using photos because their ākonga are familiar with taking and editing photos.

Their first project is the creation of a class photo journal of learning from home. Whānau have been invited to take and upload/send photos of their tamariki creating things, both the product and the process, online and offline.

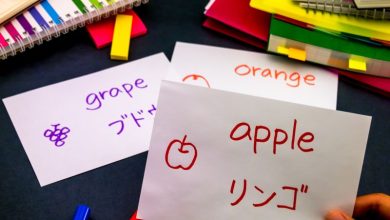

Here is an example photo for the journal.

ANNE: I’d also like to add that sometimes the learning we plan, isn’t the learning that happens, and that’s OK.

Here’s an example from my own whānau. My daughter-in-law set up a stone painting activity for our mokopuna. She imagined some colour mixing exploration. Instead Sam was fascinated with matching the lids and colours and painting himself.

Thankfully our daughter-in-law could see the value of the exploration. A space was made for Sam to determine his own pathway and no limitations were set.

Life is offering us new opportunities right now. Taking time to thoughtfully support whānau to recognise open-ended play as valued learning will take skilful communication. Āta whakaaro – to think with deliberation, considering possibilities is our guide here and our last puzzle piece.

Finding our unique puzzle piece

We have shared some of our new learnings as facilitators working alongside learning communities as they move to “learning from home”.

We are seeing such incredible innovation in our sector and are also very aware that many kaiako are looking for guidance at this time.

Our aim in introducing Āta is to encourage you to work closely with the whānau and tamariki of your communities and allow their needs, preferences and innovations to guide your teaching and learning decisions. Perhaps in giving yourself permission to focus on the practice of Āta, you will find a strong way forward for you, your ākonga, and their whānau.

NB. The tamariki’s names have been fictionalised for this post