Growing shared leadership and bicultural understandings through whakataukī

This blog is my story and shares some of my learning and views of leadership and about being a Tiriti partner as I navigate and make sense of the relationships, experiences and opportunities that present themselves.

Leadership can be about action, practice and being present in the moment. Many things come to mind when recalling stories of leadership in action; about being careful and deliberate and understanding that leadership requires decision making, courage and collective efforts.

Pōhatu’s (1994) philosophy of Āta (to be deliberate and with care) emphasises relationships and offers guidance and balance around purpose, influence and people. Āta is a philosophy embedded in Mātauranga Māori and part of a Māori world view.

The principles of Āta provide a cultural base for reflective deliberation ensuring the spiritual, emotional and intellectual levels of the education process are valued and respected. (Forsyth & Kung, 2007)

Taking care and being responsible is a constant dialogue and dance when engaging in bicultural practice. It’s a lifelong commitment and the learning happens in unexpected ways that reveal themselves at opportune times. Navigating this space with care, deep respect and reflective deliberation has supported my leadership practice.

Key responsibilities of leadership are to deeply know one’s own identity and to support others in their professional growth, creating space for their reflection, feedback and world views. As Pākehā, this also requires role modelling, advocacy and learning to walk alongside tangata whenua as a Tiriti partner. Mindful of the importance of cultural integrity, it matters to honour and valid indegenous knowledge by creating space. Understanding that everyone and everything has a whakapapa is important learning that can be enriched by reciprocity through trusting relationships.

The power of whakataukī to shape thinking and learning

Embracing Te Ao Māori as a learner and Tiriti partner can make us feel vulnerable, an example is advocating for tikanga practice whilst trying not to trample on the mana of others. One aspect of pedagogy Māori that brings inspiration is the depth and insight captured in the meaning of whakataukī (proverbs). Each whakataukī is a gift and hearing them spoken on marae and in whaikōrero (speeches) connected to the kaupapa feels like a real privilege.

Whakataukī are embedded with mātauranga and have been passed down through many generations. (Te Whāriki Whakatauki cards)

Ruru, Roche and Waitoki’s (2017) research explores the balance between Māori women’s leadership and wellbeing. Using whakataukī as overarching themes for their analysis they found that “whakataukī describe unique aspects of leadership and wellbeing from a Māori worldview. Themes include humility, collectiveness, courage, future orientations and positivity”.

The following whakataukī used in their research is about service, supporting others and harvesting an idea as an opportunity to develop a pathway for future generations (Ruru et al, 2017).

Piki kau ake te whakāro pai, hauhake tōnu iho:

When a good thought springs up, it is harvested, a good idea should be used immediately.

One particular story of leadership in action I recall is an interaction with leaders and kaiako in an early years setting, who were exploring whakataukī. As their facilitator my role was to notice, reflect, and support their professional growth and leadership in the design and implementation of their local curriculum. This example was about strengthening bicultural understandings through authentic engagement with whānau.

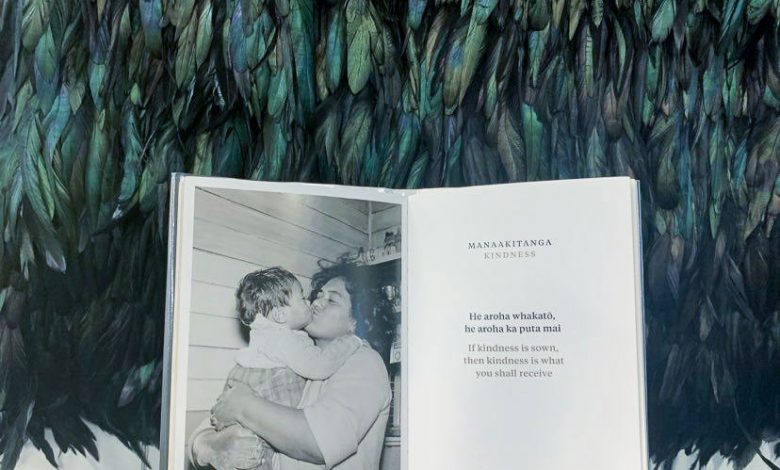

At the kindergarten I noticed that the teaching team had really connected with the book Mauri Ora – wisdom from the Māori world (Alsop & Kupenga, 2016). They were exploring the different proverbs and values in relation to their teaching. I could see they were thinking deeply about meaning as a way to support their developing understanding of Te Ao Māori. They began to unpack individual whakataukī and use them in their teaching staff room for reflection and inspiration. This was evident in their conversations and documentation.

Reflecting on this practice I noticed the depth of their engagement and a shift in kaupapa – the nature of their conversations was changing and enriched. I suggested that they could share the words and images out in the kindergarten where parents and whānau could see. They could even consider putting their book, Mauri Ora, close to where parents arrive or often spend time such as where children’s lunch boxes or bags are put away.

Returning to the kindergarten several weeks later, one of the first things that greeted me was the book of whakataukī open, and displayed alongside where parents and whānau sign in. Kaiako shared with me that not long after building up the practice of choosing a whakataukī for each day and sharing it with parents, families and whānau, a young parent, (a dad who was Māori) initiated taking on this leadership role in the kindergarten. Each morning, he would quietly come in, look through the book, choose a whakataukī, display it for other parents and whānau and talk to the teaching team about his understanding and interpretation of the whakataukī.

As an expression of authentic and shared leadership, this emerging practice became a routine. It was a wonderful way to demonstrate the concept of ako, the shared role of teaching and learning and maximising the gifts and contributions of whānau.

Kaiako then shared what they did with this gift. Each morning the teaching team and tamariki sat together, shared stories and talked about the day ahead. They took the whakataukī, chosen by the parent, and shared it with tamariki, talking about the meaning, and asking the children what they thought and understood. For example by breaking down the values of manaakitanga they could connect it to what children could see, feel and hear in the learning setting. Kaiako would ask tamariki “What do you notice?” “What does manaakitanga look like for you?”. In this way the whakataukī started to reflect in the programme.

I often reflect on the impact of that one action.

Enacting a bicultural curriculum requires understanding the significance of whakapapa as a taonga in Te Ao Māori. We have responsibilities and obligations to champion equity, use te reo Māori with correct pronunciation, and to create leadership opportunities for tamariki to share, learn about and connect with Te Ao Māori including from whānau (Ministry of Education, 2017).

Leadership is not about having answers and obtaining knowledge – it’s about conversations, reflection and creating space to hear and respect the legacies of others. This story highlights the importance of partnerships, relational trust and the opportunities for shared learning when designing a local curriculum through genuine engagement with whānau and conversations with tamariki mokopuna.

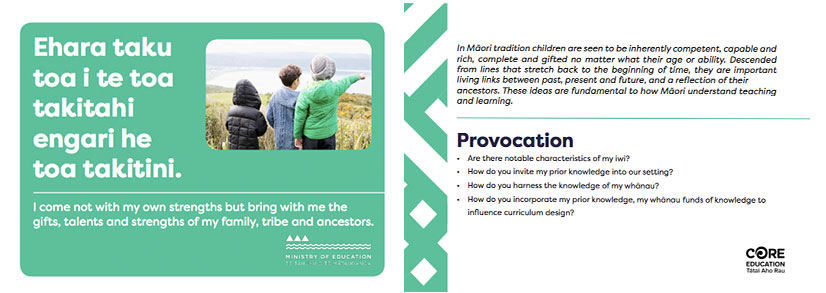

To affirm whakataukī is to accept the indigeneity of a Māori/iwi lens and invites the receiver to align their thought processes to this. This is biculturalism in its truest sense as one worldview interacts with another on the same level. Each Tiriti partner has equal status, their individual mana remains intact and intertwines to co-construct a collective understanding.(Te Whāriki Whakatauki cards)

This series of cards (image above) represent the whakataukī in the early years curriculum Te Whāriki. They are available to download from Te Whāriki Online and are a great resource to support leadership practice through conversations and critical reflection.

Download the whakataukī cards >

References

Alsop, P. & Kupenga, T. (2016). Mauri ora – wisdom from the Māori world. Potton & Burton

Forsyth, H. and Kung, N. (2007). Āta: A Philosophy for Relational Teaching. New Zealand Journal of Education Studies, 42 (1/2), 5-15.

Ministry of Education Te Tāhuhu o Te Mātauranga (2017). Te Whāriki He whāriki mātauranga mō nga mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood curriculum. Wellington, NZ

Ruru, S., Roche, M., & Waitoki, W. (2017). Māori women’s perspectives of leadership and wellbeing. Journal Of Indigenous Wellbeing – Te Mauri – Pimatisiwin, 2(1). Retrieved 17 July 2020, from https://journalindigenouswellbeing.com/media/2018/07/64.51.M%C4%81ori-women%E2%80%99s-perspectives-of-leadership-and-wellbeing.pdf.