News of a revised New Zealand history curriculum was welcomed by many, including me as an historian and someone who has worked closely with high schools and the education sector.

In particular, this seemed like an opportunity to extend the breadth of history taught, including the important stories of Aotearoa’s migrant and refugee communities.

In its present form, however, the Ministry of Education’s history curriculum consultation document falls well short.

Allowing for the fact the draft curriculum proposal is meant as “a framework” for “setting directions” and not a detailed prescription, aspects of it are nonetheless deeply worrying — not least the invisibility of the Chinese story.

With the public consultation process, that ended on May 31, it’s vital this gap is addressed.

The other New Zealand stories

The aim of history teaching should be to empower learners to think critically about the past. This equips them to understand the present and deal with the complexities of the future.

History is an interpretation of past events in as comprehensive and unbiased a way as possible. Sound history needs to have accuracy and integrity.

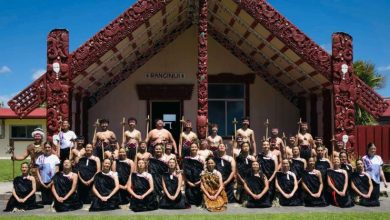

Quite rightly, Te Tiriti o Waitangi as a founding document legitimising the relationship between Māori and the Crown is central to the draft curriculum.

However, there is little mention of tauiwi, the many communities who have come to call Aotearoa home, but who do not identify as Māori or Pākehā.

The Chinese as ‘other’

I write from the experience of researching and writing New Zealand Chinese history. The Chinese have been in Aotearoa New Zealand for close to 180 years and have never been part of the binary frame of colonisers and colonised.

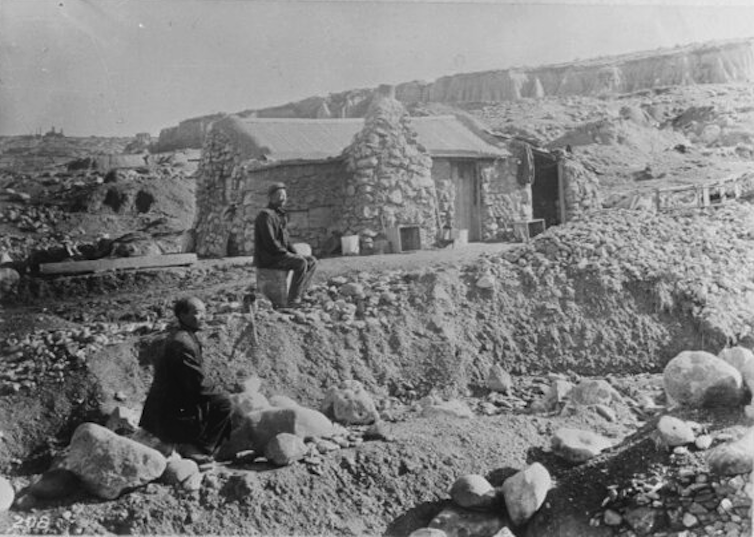

They were itinerant workers brought to the Otago goldfields and subjected to a series of anti-Chinese laws from 1881 onwards. Since the Chinese were prevented from applying for naturalisation from 1908 onwards, they could never be British subjects or be represented by the Crown.

Neither Pākehā nor Māori, the Chinese are still labelled “others”.

Relegated to the fringe of society, they had no say in the nation’s policies and could not even expect the most basic rights, from miners’ accident benefits and family reunion to health care.

They were the only ethnic group to pay a £100 poll tax for entry and had to be thumb printed on arrival and departure. Many of the arbitrary policies targeting Chinese were applied to local-born Chinese, confirming they were about race, not nationality.

Governor George Grey favoured New Zealand’s development as a “better Britain of the South Pacific” and successive New Zealand governments continued to build a white nation.

Chinese immigration was strictly controlled by tonnage ratios, quota systems, poll taxes and an English test. From the 1860s to the 1950s, the Chinese endured forced family separation in the interests of that unofficial white New Zealand policy.

A history of suspicion

The reception and treatment of the Chinese as a community is an interesting social barometer of New Zealand as a whole.

In the post WWII era of comparative plenty, New Zealand accepted refugees and orphans from many parts of war-ravaged Europe. During this period, a few hundred Chinese women and children who escaped the Japanese occupation of China in 1939-40 were allowed to stay in New Zealand.

This modest group formed the nucleus of the Chinese New Zealand community, and the Chinese finally became families instead of cohorts of bachelors.

The arrival of the “new Asians” after 1987 was a rude awakening for everyone concerned. They seemed a far cry from the low-key, docile and polite local-born Chinese New Zealanders.

Auckland suburban newspapers splashed a sensational two-page story about “The Inv-Asian” in 1993. In 2006, the magazine “for thinking New Zealanders”, North & South, featured a story titled “Asian Angst: Is it time to send some back?”

A curriculum for all New Zealanders

The proposed curriculum risks continuing this unfortunate legacy of treating Chinese New Zealanders as perpetual migrants, a label not applied to the British people who have settled in Aotearoa.

A sound history curriculum should ensure all New Zealand’s children see history as a truly relevant subject. It needs to be everybody’s story. The linkages of non-Pākehā, non-Māori history must be established within the national history framework.

Read more: The model minority myth hides the racist and sexist violence experienced by Asian women

The relationship between the Chinese (as the most distinctive, “undesirable” or “despised” immigrant group) and Māori (as tangata whenua) is arguably the most essential relationship to tease out.

The draft curriculum proposal does not specifically recognise the diversity of New Zealand society in the past or present. Without significant and explicit guidance on the histories of the many diverse communities that call Aotearoa home, the risk is they and their children will fail to see themselves in their country’s histories.

And that will make it all the harder to see themselves as an important part of their country’s future.![]()

Manying Ip, Emeritus Professor of Asian Studies, University of Auckland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.