<h2>The tide against streaming in schools is swelling.</h2>

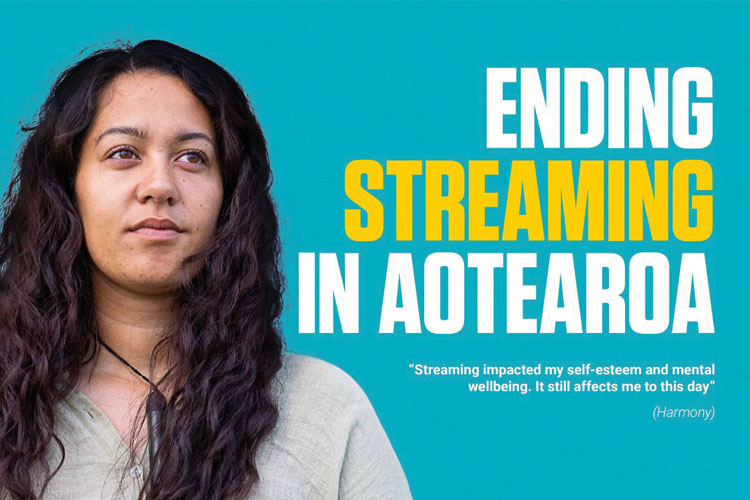

<p>In our last issue, <em>Principal Speaks</em> columnist Richard Crawford discussed the ability grouping issue, following research by Tokona Te Raki – Māori Futures Collective on <em>Ending Streaming in Aotearoa</em>. School News NZ received responses from readers also siding against the historic practice of grouping students by perceived ability that research has shown unfairly <strong>disadvantages Māori and Pasifika young people.</strong></p>

<p>In 2013, research led by University of Canterbury by educational psychologist Professor Garry Hornby, now Emeritus Professor at the University of Plymouth in the UK, condemned the practice. Research found that grouping students by ability in intermediate and secondary schools could prove detrimental to many students. Hornby said, &#8220;The findings of our research reinforce the need for schools to re-consider their practices for ability grouping and adopt strategies that will be more effective in bringing about improvements in children’s educational achievements.’’</p>

<p>And yet, the practice of streaming continued apace in Aotearoa. Indeed, it continued to such an extent that this country is believed to have one of the most highly streamed education systems in the world.</p>

<p>Included in the Education and Training Act 2020 is the requirement of school boards of trustees to honour and effect the Treaty of Waitangi in schools by achieving equitable outcomes for Māori students. Education Minister Chris Hipkins has expressed the view that streaming is inconsistent with these priorities.</p>

<p>&#8220;Teachers informally group students all the time in perfectly acceptable ways,&#8221; he said in a statement. &#8220;For example, they may focus their efforts more intensively with a small group within the class who need more attention in a particular area like reading or arithmetic.</p>

<p>&#8220;But streaming students into classes where lower overall expectations are set for some groups of learners isn’t acceptable practice.&#8221;</p>

<p>Step up, Tokona Te Raki – Māori Futures Collective, which in March, produced its report, <em>Ending Streaming in Aotearoa</em>. Research focused on the teaching of mathematics, highlighting four New Zealand schools where streaming has been recently removed, with positive outcomes.</p>

<p>“Our campaign was sparked three years ago by a school visit on a day when a number of Māori students had just been told they had been placed in a foundation maths class. We saw their anger at this decision,” said a media statement from Tokona Te Raki.</p>

<p>For its earlier research document, He Awa Ara Rau &#8211; A Journey of many Paths, Tokona Te Raki tracked over 70,000 rangatahi Māori through education and into employment. Research found streaming to be one of the most significant barriers to future success.</p>

<p>“…right now, an unfair practice that divides and labels tamariki (children) from the very first day they arrive at school is standing in the way of that vision. <strong>This practice is known as streaming,” said the report.</strong></p>

<p>“We found students are more likely to be streamed based on behaviour and assumptions, rather than genuine differences in ability. Racism, deficit-thinking and stereotyping mean educators are less likely to place Pākehā students in foundation classes and low streams. These decisions limit rangatahi <a class="wpil_keyword_link" href="https://www.schoolnews.co.nz/2015/10/developing-opportunities-at-school-with-a-view/" title="opportunities" data-wpil-keyword-link="linked" target="_blank">opportunities</a> and pathways.</p>

<p>“Many students who were told they’re low ability, do not or cannot enter full NCEA courses. The impact of streaming narrows career choices to low skill, low paid, and high-risk jobs and employment. <strong>We know that it is bad for everybody, but it is especially bad for Māori and Pasifika students. This is systemic racism in action.”</strong></p>

<p>Tokona Te Raki included Hastings Girls’ High School, Wellington High School, Horowhenua College and Inglewood High School in Taranaki in its dedicated <em>Ending Streaming in Aotearoa </em>research project. These schools have abolished streaming and seen students improve academically across the board, especially Māori and Pasifika students, by finding alternative systems of teaching that brought teachers and students closer together.</p>

<p>“They used tools that brought teachers and students closer together &#8211; like learning more about each child’s passions and goals for maths, and scrapping arbitrary deadlines to assess students when they were ready. They have seen more students moving into Year 11 and Year 12 maths and students&#8217; self-belief, confidence and motivation improve,” says Tokona Te Raki.</p>

<blockquote>

<p>“We need to make sure this outdated practice is stood down from all classrooms.”</p>

</blockquote>

<figure id="attachment_20385" aria-describedby="caption-attachment-20385" style="width: 225px" class="wp-caption alignleft"><img class="size-medium wp-image-20385" src="https://www.schoolnews.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Piripi-Prendergast-2021-225x300.jpg" alt="" width="225" height="300" /><figcaption id="caption-attachment-20385" class="wp-caption-text">Piripi Prendergast</figcaption></figure>

<p>A campaign petition had gathered over 2755 signatures by mid-July. A rap track, ‘Don’t Run’ featuring Syd Diamond and produced by DJ Severe, was released on the back of the report, to connect the anti-streaming movement message with rangatahi. </p>

<p>School News NZ spoke with campaign champion, Tokona Te Raki – Māori Futures Collective’s Piripi Prendergast, who said the Ministry of Education has given the campaign its backing. “The Ministry came to us and said they would like us to lead a collaborative response to ending streaming, so let’s do this as a collaborative process.”</p>

<p>That collaboration began on May 25 with a nationwide hui, held in Ōtautahi Christchurch. It brought together over 60 individuals from across the education sector to kōrero.</p>

<p>“We invited national leaders of key stakeholder organisations to a meeting,” says Prendergast. “Twenty-two organisations were represented including ERO, the Ministry of Education, the Principals’ Federation, iwi leaders, teachers, race relations and all the education unions. It was a big day!</p>

<figure id="attachment_20386" aria-describedby="caption-attachment-20386" style="width: 300px" class="wp-caption alignright"><img class="size-medium wp-image-20386" src="https://www.schoolnews.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Hui13-300x224.jpg" alt="" width="300" height="224" /><figcaption id="caption-attachment-20386" class="wp-caption-text">Kōrero at the Ōtautahi Christchurch hui.</figcaption></figure>

<p>“People were not spoken at; they worked in groups and at the end of the day a call to action for all organisations to go back and work out what they would commit to doing.”</p>

<p>Prendergast said one of the outcomes of the hui was the decision to create a design team. “The question is now ‘how do we make the shift?’ That is why we have set up a design team to come up with a blueprint.”</p>

<p>It will consist of up to 20 members and meet twice a month in Christchurch, starting in August, he says. “We have been absolutely amazed by the calibre of people who have put their names forward to be on the design team. The Ministry of Education has put forward three people to come on board, for example.” He says the team will include principals, researchers and rangatahi. </p>

<blockquote>

<p>“The response has been very, very good. To have such a number of large organisations committing to ending streaming has been amazing. And a number of them have gone even further by committing staff members twice a month to work with us!”</p>

</blockquote>

<p>Most pressing, says Prendergast, is the need for a definitive date to be set for ending the controversial practice. “We want there to be a date put on when streaming will end in Aotearoa,” says Prendergast. “Let’s say, by 2030, this will no longer be allowed to happen. I think it should go the way of corporal punishment; it was something that was always done and then it was banned so it can’t happen anymore. I think that’s what it will be like with streaming.”</p>

<p>Opposition to ending streaming, Prendergast says, largely comes from parents of children who have been streamed into what are often deemed ‘top’ groups. “Parents say, ‘what about the top kids?’ Well, there is substantive research currently coming out of England, through Taylor &; Francis, which shows that when so called ‘top students’ are put into a mixed ability setting, they are actually doing better. It’s quite ground-breaking research.”</p>

<p>CORE Education is one of the many organisations to come out in support of the campaign, saying it, “Congratulates and stands alongside Tokona Te Raki as they champion a system response to ending streaming in Aotearoa.” CORE’s Tumu Whakarae, Dr Hana O’Regan said, “We know first-hand that it can be hard to do things differently, and that learning communities will need support to look with fresh eyes at how they can “de-stream” so that all learners have the best chance of success.”</p>

<p>Prendergast says the role of the design team will be to pave a practical path for a future where streaming no longer exists. “Yes, it will need a lot of resourcing and that’s what the design team is there to look at. Working in communities, not just as ad-hoc schools, is the way to go about this.</p>

<p>“Let’s do it as a collaborative process. So many organisations, including the Ministry, are taking action and actively want us to get rid of streaming, so let’s set a date and get on and do it!”</p>

NZEI Te Riu Roa is considering legal action against the government for the disestablishment of…

NZQA is implementing AI-marking for all Year 10 written assessments from this year onwards, following…

Teaching personal financial responsibility isn't enough. Children should be taught broader economic context, argue New…

When students can't hear the teacher, they can't learn properly. Sound quality matters in education…

The Garden City is rich with learning opportunities, no matter what subject or part of…

Teaching Council of Aotearoa launch school leaders’ stories project with Unteach Racism to challenge institutional…

This website uses cookies.