Universities show dangers of working from home for women’s careers

If one possibly positive thing came out of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was the impetus it gave to letting people work from home.

Many see working from home as benefiting women workers. The logic is they can combine a career with the responsibilities of looking after children. But not enough thought has been given to how this could make things worse, not better, for many women.

We wanted to know how working from home during the pandemic affected men and women, including their productivity at work. We surveyed 11,288 people working in 14 universities across Canada and Australia, including 3,480 academics.

Our interest was sparked by an early observation by an editor of a British scholarly journal that journal submissions by women academics had fallen significantly.

This observation has been confirmed by several systematic studies that show declines in research outputs by women academics.

What did the study find?

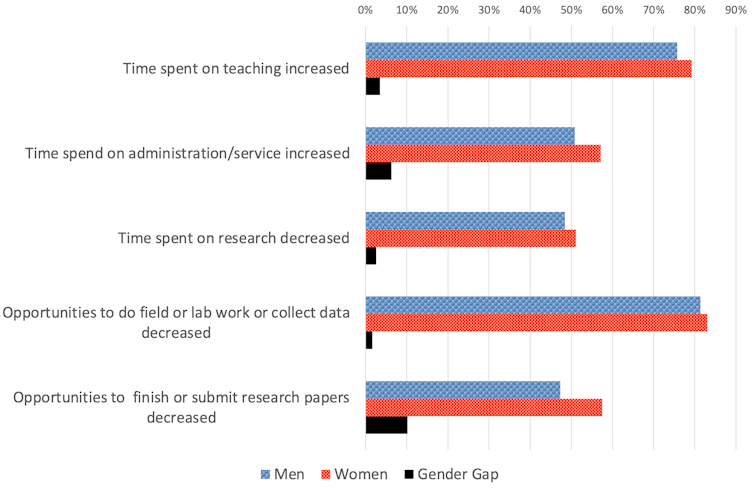

Our own study of academic staff in the survey showed the same thing. Indeed, this difference in opportunities to submit research for publication was the biggest difference between the experiences of men and women during pandemic-induced lockdowns.

Women ended up facing increased teaching loads and doing more administration work more often than men. Women were also more likely than men to spend less time on research.

But the gender differences for these tasks were not as large as those in applying for research funding or submitting articles to peer-reviewed journals. These are the measures by which academic careers stand or fall these days.

What seems to be happening is that both men and women were forced to do more of their research at home. The difference was that women had less chance than men to put in the sustained time to produce good, publishable research. In our study, especially when children were around, women had more difficulty finding the vital “thinking time” needed for good research.

Ideally, men would assume an equal share of domestic responsibilities when working from home. But that hasn’t happened.

The future looks worse

Without confronting the problem head-on, universities are likely to make the problem worse.

We found most university staff want to work from home more than they were allowed before the pandemic.

Women tended to want more of this than men. That would, however, make them less visible in the physical office. And that, in turn, could reduce their perceived productivity.

Many universities can see the work-from-home trend as providing opportunities to save money. They can do this by getting rid of private offices and shifting academics into shared spaces. It’s a trend that started before the pandemic.

But when academics are on campus, a private office, not a shared space, is needed to do online teaching or research that requires thinking time.

Moreover, universities are increasingly tempted to reduce academics’ access to sabbaticals. Historically, these periods of study leave have been the best chance to find the thinking time to do good research. Now, though, it’s becoming less of an “entitlement” and more of a “privilege”, available to fewer researchers each year.

As sabbaticals become less available, women will find it much harder than men to make up for the lack of sustained thinking time. Their real productivity would be lower than men’s.

It’s the same for many white-collar workers as well

What we’ve described isn’t just a problem for academics. It’s a problem in any white-collar occupation in which “knowledge work” is performed.

In many jobs sustained knowledge work — that is, work involving long periods of concentration, and hence a good amount of thinking time — is needed to develop the best ideas. Most managerial jobs, and many professional and administrative jobs, involve and require some periods of sustained knowledge work.

But especially since the pandemic, both in the public and private sector, most staff want to be able to work from home some of the time. This is not just a pandemic phenomenon. Workers genuinely like not having to spend hours commuting every day.

Employers, too, now figure employees can be just as, if not more, productive at home. Employers are already taking advantage of “hybrid working”. They are putting more people into “hot desks” or other co-working spaces to reduce physical office costs.

That might sound fine, until you realise that the opportunities for, and the outcomes of, sustained knowledge work — the stuff that will get you recognised and promoted — will be gendered. It will be harder for women than men to schedule in the necessary thinking time, especially at home.

Where to from here?

Many of the slow advances women have made in some knowledge work occupations in recent times may be lost if they have less opportunity to get the sustained thinking time that translates into performance.

If women are to have a fair go in white-collar jobs in the future, then employers will need to rethink their post-pandemic strategies for saving money. Shared spaces may be good for the accommodation budget, but they’re not so good for the individuals concerned or for their contribution to organisational productivity.

Where unions represent those workers, they need to resist the closure of office facilities that can be critical for sustained knowledge work.

Governments need to be more active in supporting widespread, affordable, accessible, quality childcare.

Much has been written about how the economic response during the pandemic disadvantaged women. But worse may follow. We need to design to offset, not to compound, the problems that could come from more working from home.![]()

AUTHORS: David Peetz, Professor Emeritus, Griffith Business School, Griffith University; Kim Southey, Senior Lecturer in Management, University of Southern Queensland; Marian Baird, Professor of Employment Relations, University of Sydney; Mojan Naisani Samani, PhD Candidate, DeGroote School of Business, McMaster University; Rae Cooper, Professor of Gender, Work and Employment Relations, ARC Future Fellow, Business School, co-Director Women, Work and Leadership Research Group, University of Sydney; Sara Charlesworth, Professor, School of Management, RMIT University; Shelagh Campbell, Associate Professor, Ethics and Labour Relations, University of Regina, and Susan Ressia, Senior Lecturer, Employment Relations, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.