The top three skills needed to do a PhD are skills employers want too

More and more people are applying to do a PhD. What many don’t know is it takes serious skills to do one – and, more importantly, complete it.

Lilia Mantai, Senior Lecturer and Academic Lead, University of Sydney and Mauricio Marrone, Associate Professor, Macquarie University analysed the selection criteria for PhD candidates on a platform that advertises PhD programs. Their analysis of thousands of these ads revealed exactly what types of skills different countries and disciplines require.

Why do a PhD in the first place?

People pursue a PhD for many reasons. They might want to stand out from the crowd in the job market, learn how to do research, gain a deeper expertise in an area of interest, or pursue an academic career.

Sadly, too many PhD students never finish. The PhD turns out to be too hard, not well supported, mentally taxing, financially draining, etc. Dropping the PhD often means significant financial loss for institutions and individuals, not to mention the psychological costs of other consequences such as low self-esteem, anxiety and loneliness.

Our society and economy can only benefit from a better-educated workforce, so it is in the national interest to manage PhD intakes and be clear about expectations. The expansion of doctoral education led to a more competitive selection process, but the criteria are opaque.

To clarify PhD expectations, we turned to a European research job platform supported by EURAXESS (a pan-European initiative by the European Commission) where PhD programs are advertised as jobs. Required skills are listed in the selection criteria. We analysed 13,562 PhD ads for the types of skills different countries and disciplines require.

We made three specific findings.

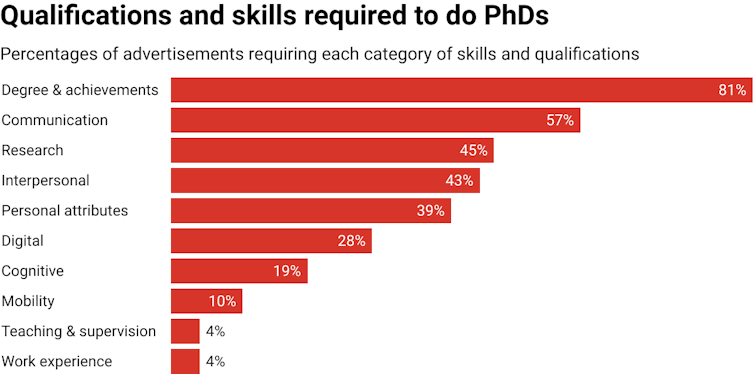

1. Top 3 skills needed for a PhD

It turns out that it takes many so-called transferable skills to do a PhD. These are skills that can be translated and applied to any professional context. The top three required skills are:

communication – academic writing, presentation skills, speaking to policy and non-expert audiences

research – disciplinary expertise, data analysis, project management

interpersonal – leadership, networking, teamwork, conflict resolution.

Trending skill categories are digital (information processing and visualisation) and cognitive (abstract, critical and creative thinking and problem-solving).

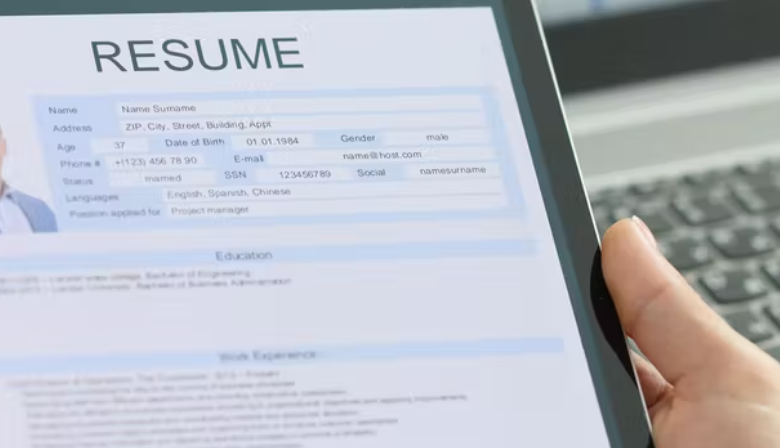

Previous research shows transferable skills are requested for post-PhD careers, including both academic and non-academic jobs. Our research shows such skills are already required to do a PhD. Those keen to do a PhD are well advised to provide strong evidence of such skills when applying.

2. Skill demands vary by country and discipline

Skill demands significantly differ by country and discipline. For example, 62% of medical science ads mention interpersonal skills. This is twice as often as in biological science ads. Digital and cognitive skills score much higher in the Netherlands than in other countries.

Our research article reports on 2016-2019 data and the top five represented countries (Netherlands, Germany, France, Spain and the UK) and the top five represented disciplines (biological sciences, physics, chemistry, engineering and medical sciences). However, you can use this tool for granular detail on 52 countries – including non-European countries like Australia, New Zealand, the US, etc. – and 37 disciplines included in the data sample. For continuously updated data, please visit https://www.resgap.com/.

3. PhD expectations are rising

We see a rise in PhD expectations over time (2016-2019) as more skills are listed year on year. The publish or perish culture prevails and rising demands on academics have led to calls for more engaged research, collaborations with industry, and research commercialisation.

PhD students get accustomed early to competitiveness and high expectations.

Research-based learning needs to start early

These insights have implications for pre-PhD education and pathways. Undergraduate and postgraduate degrees can further promote PhD readiness by embedding authentic hands-on research with academic or corporate partners, either as part of the curriculum or as extracurricular activities.

Many postgraduate degrees offer authentic research project work opportunities but are shorter. Those entering the PhD without a postgraduate degree miss out on developing essential research skills.

Authentic research experiences need to happen early on in higher education. Organisations like the Council on Undergraduate Research (CUR), the Australasian Council for Undergraduate Research (ACUR) and the British Conference of Undergraduate Research (BCUR) are designed to support institutions and individuals to do this effectively. They showcase great models of undergraduate research.

To get a good idea of what undergraduate research looks like, start with this comprehensive paper and catch up on undergraduate research news from Australasia.

We know research-based learning develops employability skills such as critical thinking, resilience and independence.

Embed career development in PhD programs

Doctoral training needs to take note, too, if it is to further build on the skill set that PhD applicants bring with them.

The good news is doctoral education has transformed in recent decades. It’s catching up to the call for better-skilled graduates for a range of careers. The training focus has shifted towards generating practice-based and problem-solving knowledge, and engaged research with other sectors.

Some institutions now offer skill and career training. Generally, though, this sort of training is left to the graduates themselves. Many current PhD candidates will attest that the highly regulated and tight PhD schedule leaves little room for voluntary activities to make them more employable.

Most PhD candidates also know more than half of them will not score a long-term academic job. Institutions would serve them better by formally embedding tailored career development opportunities in PhD programs that prepare for academic and non-academic jobs.

It’s not only PhD graduates’ professional and personal well-being that will benefit but also the national economy.![]()

AUTHORS: Lilia Mantai, Senior Lecturer and Academic Lead, University of Sydney and Mauricio Marrone, Associate Professor, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.