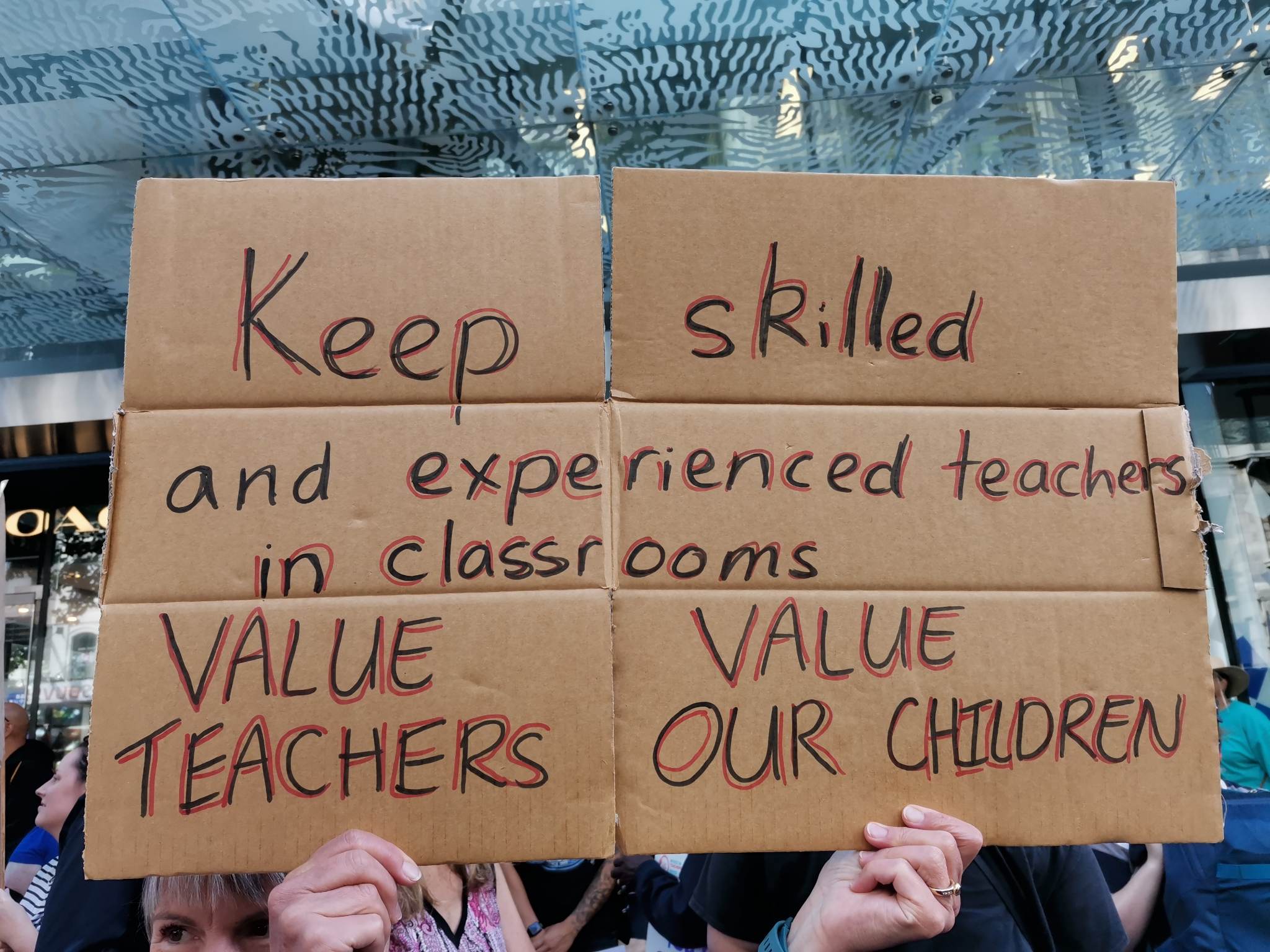

Image taken at Teacher's Strike, March 16, Auckland CBD | Image by Naomii Seah

<p>Education often becomes a “political football” in election years, with parties promising their educational policies will lead to the best outcomes – but what does the sector really need to support the next generation of New Zealanders? <em>School News</em> asks the educators themselves.</p>

<p><a href="https://www.schoolnews.co.nz/latest-print-issue/" target="_blank" rel="noopener">Read the Term 2 edition of <em>School News</em> HERE</a></p>

<p>In recent months, the education sector has been in the spotlight as schools come under scrutiny. Post-pandemic, students are appearing less engaged, have more pastoral and support needs, and are generally achieving less highly. For their part, teachers are overwhelmed as they’re being asked to take on higher workloads, provide social support and implement curriculum changes. Classroom sizes are also increasing, and teacher shortages are putting more pressure on the situation. </p>

<p>Earlier this year, an estimated 50,000 teachers – primary, secondary, area and ECE – were compelled to strike over poor working conditions. Many teachers expressed frustration over the lack of support and resourcing from the Ministry of Education. For the wider public, concerns over truancy and barriers to education are growing. Additionally, issues around education are intersecting with wider issues such as the cost of living and transport. </p>

<figure id="attachment_26392" aria-describedby="caption-attachment-26392" style="width: 1024px" class="wp-caption alignnone"><img class="size-large wp-image-26392" src="https://www.schoolnews.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/SN61-EDU-Special-Report-2-1024x768.jpg" alt="Stike" width="1024" height="768" /><figcaption id="caption-attachment-26392" class="wp-caption-text">Image taken at Teacher&#8217;s Strike, March 16, Auckland CBD | Image by Naomii Seah</figcaption></figure>

<p>All this discourse about education is taking shape during an election year. To add fuel to the fire, Chris Hipkins, former Education Minister, has just stepped into the role of Prime Minister. Although new to the job, Hipkins’ perceived inaction on issues of education has left many in the sector feeling abandoned. Many educators expressed hope for the future of education following the appointment of experienced principal Jan Tinetti to the role of Education Minister. However, since the beginning of the year when Tinetti stepped into the role, the new minister has faced criticism over the collection and release of attendance data, and the prolonged collective agreement negotiations between the <a href="https://www.schoolnews.co.nz/2023/10/student-wellbeing-in-education-a-new-report-from-moe/" target="_blank">MoE and education</a> unions. At the teacher’s strikes on March 16, Tinetti was booed by the crowd that she had previously marched with. </p>

<p>Education has been an election issue in the past, and this year, it’s looking like education will be a key issue at the polls. In this term&#8217;s special report, School News unpacks the history of education policy in New Zealand; we also look at what education policies have been unveiled so far, and ask educators what they really need from our elected leaders. </p>

<p><strong>Education as election policy </strong></p>

<p>Education is a powerful tool. Often, curriculum and other education policy reflects the predominant values and ideology of the time. New Zealand’s modern school system has its roots in the British colonial system, and over the years, reforms have altered our education system in line with our evolving national identity. </p>

<p>In the 1980s, during a series of broad liberal reforms, education came to be viewed as a market commodity. The Education Act of 1989 reflected this ideological change, decentralising education administration and creating the Ministry of Education to oversee policy. Schools became locally administered, with the belief that self-managed schools would improve educational outcomes by creating a competitive environment. School results would then create accountability. The idea was that the education market would follow the model for other goods and services – “customers” or students would flock to the best schools. </p>

<p>Since this period of liberal reform, the school system in New Zealand has remained largely the same, and has faced the same general issues. Māori and Pasifika continue to underperform in the system, signalling an in-built inequity that has yet to be effectively addressed. For decades, there has been a worrying downward trend in literacy and numeracy rates, leading to educational policy such as National Standards and continuing achievement standard reforms. </p>

<p>Although the liberalisation of the education system was a Labour policy, the National Standards, introduced by National in 2009, is a faint echo of the ideology that transformed our educational system into a competitive market. With its introduction, Primary and Intermediate schools had to report the progress of their ākonga in reading, writing and maths; this would be judged to a given standard. </p>

<p>In 2017, then Labour education spokesperson, Chris Hipkins, said of the National Standards expansion that “Kids in New Zealand are over assessed. What we need is less reporting, more teaching.” In 2020, the Labour government scrapped these standards, stating it would “give teachers more time with students”.</p>

<figure id="attachment_26394" aria-describedby="caption-attachment-26394" style="width: 1024px" class="wp-caption alignnone"><img class="size-large wp-image-26394" src="https://www.schoolnews.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/SN61-EDU-Special-Report-3-1024x768.jpg" alt="Strike" width="1024" height="768" /><figcaption id="caption-attachment-26394" class="wp-caption-text">Image taken at Teacher&#8217;s Strike, March 16, Auckland CBD | Image by Naomii Seah</figcaption></figure>

<p>In 2019, Labour’s Tomorrow’s Schools review looked at the overhaul of the education system in 1989, and addressed some of the weaknesses of our current school system. In a press release, then Education Minister Chris Hipkins said the review would lead to a “reset of the way schools are led and supported.</p>

<p>“It addresses the limiting factors, inconsistencies and inefficiencies in administration, governance and management that have built up over time, drives excellence and sets the compulsory schooling system up for the next 30 years.”</p>

<p>Reforms will include the establishment of an Education Service Agency, that aims to create a “more responsive, accessible and integrated local support”. </p>

<p>Although these policies were well received, it wasn’t long before Labour faced criticism over the post-pandemic decline in attendance and achievement in our schools. </p>

<p>In an echo of policies past, National and ACT parties are proposing a more detailed reporting system for schools over attendance data. Erica Stanford said that National would require the Ministry of Education to publish attendance data in “real time”. ACT Party spokesperson said there should be mandatory daily attendance reporting and fines for parents whose children miss school. This goes against the ERO report which said that punitive measures for whānau whose tamariki missed school would likely worsen outcomes, as those missing school were more likely to be facing other barriers such as cost-of-living and transport. </p>

<figure id="attachment_25384" aria-describedby="caption-attachment-25384" style="width: 2560px" class="wp-caption alignnone"><img class="size-full wp-image-25384" src="https://www.schoolnews.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/AdobeStock_191616719-scaled.jpeg" alt="" width="2560" height="1201" /><figcaption id="caption-attachment-25384" class="wp-caption-text">AdobeStock by tinyakov</figcaption></figure>

<p>Apart from these policies on attendance reporting, National has also recently unveiled their new education policy, “Teaching the Basics Brilliantly”, which has been widely criticised by educators as a return to the failed National Standards policy. If elected, National has promised to overhaul the education system. They would mandate an hour each of reading, writing and maths teaching for students Years 0 – 8, and require two tests a year for children Years 3 to 8. The aim of these policies was to improve the numeracy and literacy of children in New Zealand. </p>

<p>At the time of writing, no other political parties have created tangible education policy, though Labour has indicated that they would continue to support initiatives such as free lunches in schools, to help ease barriers to education caused by external factors such as the cost-of-living. </p>

<p><strong>What educators want </strong></p>

<p>As Lynda Stuart, May Road School Principal and NZEI Te Riu Roa principals’ negotiator, put it in the October 2014 issue of North &; South: “I think educators know what they’re doing in New Zealand – and I don’t think they’re asked often enough about what should happen. When we have that conversation, when our politicians really listen to what we’re saying, then we will have the most wonderful education system in the world.”</p>

<h4>In the spirit of Stuart’s words and the sentiment at the teacher’s strike – listen to educators – S<em>chool News</em> put out the call, and asked teachers what they really wanted to see this election year. </h4>

<p>One theme of the responses to our survey was that schools were being given too much responsibility, and were expected to fix social issues beyond their scope. One respondent noted that “it has never been an educator’s responsibility to get tamariki to school. The educator’s role begins once the child enters the gate.” Another respondent agreed, noting that “employment of people in roles of truancy officers are at the opportunity cost of employing more teaching or support staff or providing more funding”. Yet another believed that truancy stemmed from poverty, and more should be done outside of education policy to address our attendance issue.</p>

<blockquote>

<p> On the curriculum changes, one respondent said “Give us a serious pay increase and time allowance to really invest the quality that such a curriculum deserves”. </p>

</blockquote>

<p>Teachers at the strikes in March held similar sentiments. Sav, a secondary school teacher, said she was unsure what party to vote for in the coming election as none of them had “/a clear pro-teacher stance.”</p>

<p>Jackie, a secondary school teacher attending the strikes, noted that “There’s a lot of demands for reports, for results, for self-reviews, this and that. We’re the ones doing the mahi in front of the students, yet [the government is] demanding things that take up a lot of time from our teaching&#8230; at this stage it’s hard [to know who to vote for] – who&#8217;s actually going to listen to us?”</p>

<p>Ana, Jackie’s colleague, added that in recent months the education sector had lost a lot of faith in the Labour administration, making it a tough call for the upcoming election. </p>

<p>Jason, another secondary school teacher with more than two decades of experience, agreed, noting &#8220;We have to do a lot of reporting back and data analysis, and it doesn’t make a difference.”</p>

<p>From these responses, it’s clear that for many of the hot-button issues in education, teachers agree: give schools and educators more resources, more social support and PLD for changes in the curriculum. Support tamariki and rangatahi and whānau doing it tough in the post-pandemic economy through economic and social policy. Decrease class-sizes and instate workload controls so that ākonga can have the best education possible. Decrease reporting requirements, and put the focus back on those who matter: our rangatahi and our tamariki, the future of the nation.</p>

<p>Through various surveys, news articles, radio interviews, union media releases and more, educators and teachers have been repeating themselves time and again on their needs, and in turn the needs of the education sector. Now, it’s up to those gearing up for the upcoming elections to listen.</p>

EXCLUSIVE: Teachers used to be paid two to three times more than minimum wage workers,…

After an “overwhelming” vote to reject the latest Government offer, secondary school teachers will begin…

Second-language learning should be compulsory, says a new report from a forum bringing together academics,…

A new entitlement aimed to improve access to learning support coordinators for schools with students…

Educators have raised questions about the Ministry of Education’s new secondary school subjects, set to…

Professional learning and development (PLD) for teachers needs to be higher impact for teachers and…

This website uses cookies.