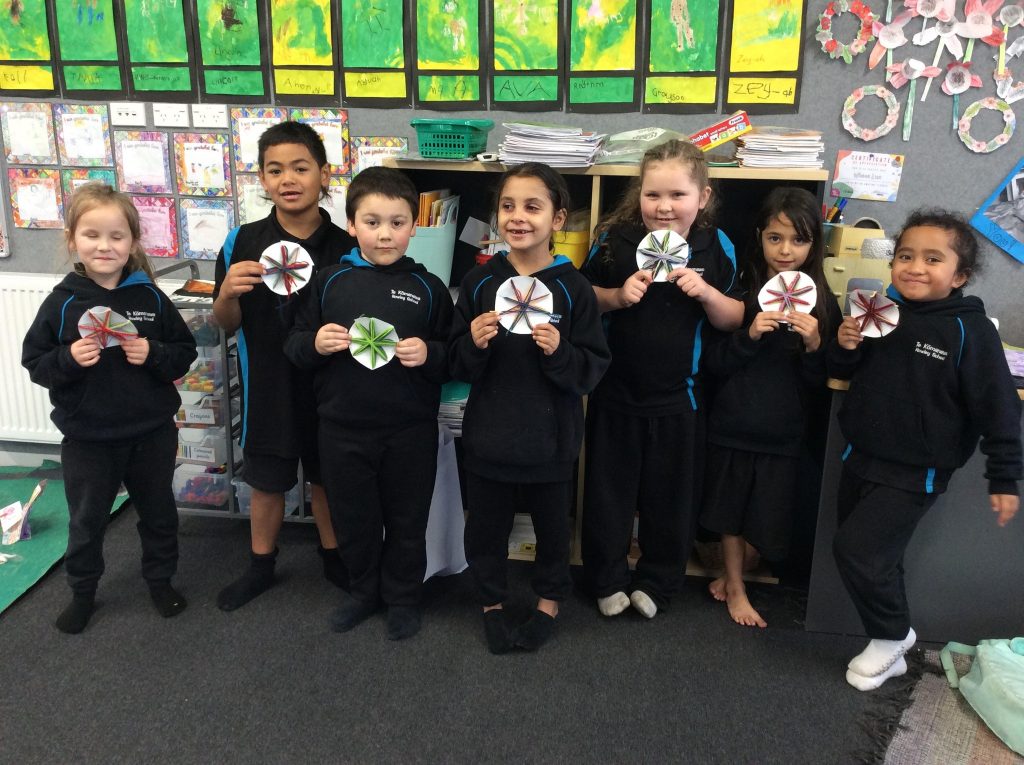

Principal Graeme Norman of Te Kōmanawa Rowley School addresses equity, inclusion and access in this Term’s edition of Principal Speaks.

I wanted to take this opportunity to talk about equity in education. There have been concerns about inequities in funding for primary schools for a long time. While generally our system works, disparities in funding and resourcing can contribute to unequal opportunities and outcomes for students.

Read the Term 3 edition of School News HERE

Despite efforts to create an equitable system, I still have concerns about funding inequities. I would argue that the current funding system is not sufficient to address the underlying disparities in resources and opportunities between schools. I acknowledge that additional funding or resourcing alone may not be enough to tackle the complex issues that contribute to inequity in education outcomes for all.

Our system talks about equity, but I don’t believe that it is totally equitable for everybody. We need to be looking at this, and addressing it within the education system, creating an even playing field for everybody.

Currently, we do not have equal access to funding and resources which ensure the children in our care get a good education. My wish is for anyone from anywhere – any economic, social background, any cultural background – to have equitable access to education in New Zealand.

I have been in education since 2002, with the past nine years as principal. Currently, I’m at Te Kōmanawa Rowley School. Our school is in a low socioeconomic area. During my time here as principal, I’ve seen the inequities of our school system first-hand.

One of my observations is that money is distributed inequitably under our current model. The equity funding system treats one low socioeconomic school much the same as another. It doesn’t matter what area you are from or what needs there might be in your community, current funding models don’t look adequately at the needs of specific schools.

Our school needs more Learning Support Assistance. Currently, we have more than half our school on our support register, but this is not recognised in the current system, so we need to fund eight LSAs to support our children. Because we see children’s learning and wanting to be at school as a priority, we must sacrifice other things. I recognise that we do get more money through the equity system but it’s not enough to cover these costs.

Another example of inequity in our system is that we don’t have access to a Kāhui Ako and cannot join a Kāhui Ako. I came to this school just after they stopped letting new schools join. There is extensive funding and resources that aren’t available to us because of this – if we were in a Kāhui Ako we would be able to access more resources and we could get a Learning Support Coordinator. We have students with very high needs, and they would benefit from having access to these resources, yet I cannot. How is this fair and equitable?

There are also regional specific needs that aren’t addressed through the current system. It doesn’t matter if you’re in Auckland, Wellington or Invercargill, everyone gets the same. Everyone’s needs, though, are different and this should be considered. In Hawkes Bay at present, for example, they should have a different funding model that adapts to needs following the trauma of the cyclone. This kind of allowance needs to be built into the system, rather than as a one-off disaster response. By doing this we would make it more equitable for the children in disaster affected areas for a number of years.

Within regions, there can be variations in the needs of each school community. We are in a low socioeconomic area, but our school operates within a specific context that creates unique needs. These needs may be different from a school operating on the other side of town that is of similar social economic background.

An example of this is the composition of our student body. Although Te Kōmanawa Rowley is a school in Christchurch, we have a very high Māori and Pacific roll, with 40 percent Pacific and 38 percent Māori. That’s unusual in Christchurch, or even in the South Island. This means the needs of the schools are different, as we cater for children from different cultural contexts and try to adapt our programme. An example of this is we run Gagana Samoan lessons across our school.

We’re in a cost-of-living crisis, which affects everyone. But for the lowest socioeconomic where there’s no disposable income, it’s hitting the hardest.

The barriers we see for these families sending their children to school are immense and varied. We’re lucky that we get school lunches, but there are schools down the road that don’t, though they have children in need. Even some schools considered high decile under the old system aren’t getting what they need to support their families in this economic crisis. To make it equitable, everyone should get school lunches. That’s how it’s done around the rest of the world. To be truly equitable, people need equal access.

Currently, I have children still coming to school in shorts and T-shirts, and we have had three days in a row of 0-degree starts. Sometimes parents aren’t sending their children because they don’t have the uniform or the shoes – even though we provide them for free. This could be because they’re embarrassed, afraid or unsure how to ask for help. Because of that, their children are missing out. I can knock on the door and give them a uniform, or even knock on the door and ask what the barriers are, but I don’t have the time to personally go in every instance.

By creating a relationship with that family and a local solution for the problem we have started solving some of these issues.

Earlier this year there was money given out to services to help with attendance. At Te Kōmanawa Rowley School we have put a lot of money into improving our attendance rates. Over the past three years, we have lifted our attendance rate from 40 to 60 percent, to currently being at 83 percent. This was done by using solutions that worked for our community. This comes at a cost, though, and funds that could have been used elsewhere have had to be diverted to this. Teachers have had to spend more time making resources that could have been brought and I have had to work longer hours to catch up on my core work.

To make it equitable from one side of town to another, solutions need to be local. We spend so much time building trust with the community, and that’s important. When we go and knock on their door, they’re more likely to open it than they are to a stranger from attendance services. We have a lot of families who have English as their second language, so communication in English can be challenging. I have people who can come along with me and interpret so the right message is getting across. To bring an interpreter, though, takes money and resources. And attendance services may not know which households need an interpreter. We know our communities and how best to serve them so give us the money to come up with local solutions.

The circumstances of each whānau are different too, even among families in ostensibly similar socioeconomic brackets. In some families, parents may work night shifts, and home visits at certain times just aren’t possible. Other families may be struggling to find employment. And with each of these scenarios, there can be quite a difference in disposable income, which needs to be accounted for when finding solutions to help these families.

These are just some examples of how local principals know best where the money needs to be invested so that it can be used wisely and effectively to come up with solutions to help with attendance.

Another area of inequity I believe needs to be addressed is that of class size. Under the current staffing model smaller schools lose out. We need to hold 25 students before we get another teacher whereas a bigger school only needs to hold on to three students before they get .1 of a teacher. For every 15 students they hold, they can employ .5 of a teacher to help take the pressure off. Currently, I have 150 students with seven teachers in their classrooms.

Our senior classes currently sit at 28 and 29 students. If I get another 5 senior students next term this will mean these classes will end up with 31 students in them each. It’s only at 175 students that I get another teacher.

It’s not equitable, particularly if I get an influx of students in one year group where the class may already be at capacity. With the transient nature of low socioeconomic schools, classes sometimes balloon to 35 or 36. Yet we don’t get another teacher. So while there is a plan to reduce class sizes, it needs to be made equitable for all schools. The current way teachers are funded needs to be looked at and addressed to make it equitable for all.

Finally, although we’re slowly adapting to Māori learners, learners from Pacific nations, and learners from all over the world, our school system is still focused on the European model. We’re trying to make people fit into a system that wasn’t made for the context of Aotearoa New Zealand as a multicultural society. The whole curriculum, the whole education system needs to be examined and adapted to make it a New Zealand system. We need to get right away from the Eurocentric system and start again, with a system that’s fit for purpose here. Only then can it be truly equitable and accessible for everybody.

We want children at school, but then we try and educate them in a system not fit for purpose and tell them they’ve failed when they are not meeting a standard. Would you want to be educated in a system that tells you that you’re failing because it is forcing you to fit into their way? I believe the solution lies in putting trust back into teachers. We’re the ones seeing children grow and improve. We don’t need tests, we just need to see that growth, what’s happening with each individual learner. That requires trust in our teachers to make good judgement.

To address these needs, I believe that a higher degree of trust is needed between the Ministry and local principals. Currently, there are a lot of hoops that principals and boards must go through to secure any extra funding to meet needs as they come up. To achieve a more equitable system, we need to make it easier to access funds and resources and ensure that these funds and resources are going to the right place.

For me, true equity is about responding to specific needs. That means regional-specific needs, school or kura-specific needs, community-specific needs, whānau-specific needs and individual learners’ specific needs. One shoe will not and does not fit all.