Literacy is a foundational component of learning which unlocks the rest of the curriculum.

Ensuring students are appropriately literate at each stage of school sets them up for future success in their NCEA years and beyond. Recent changes to the curriculum are designed to help New Zealanders reach literacy goals.

The refreshed English learning area leans on the concept of structured literacy, a teaching practice that has both local and international evidence for its efficacy.

Read the latest print edition of School News HERE

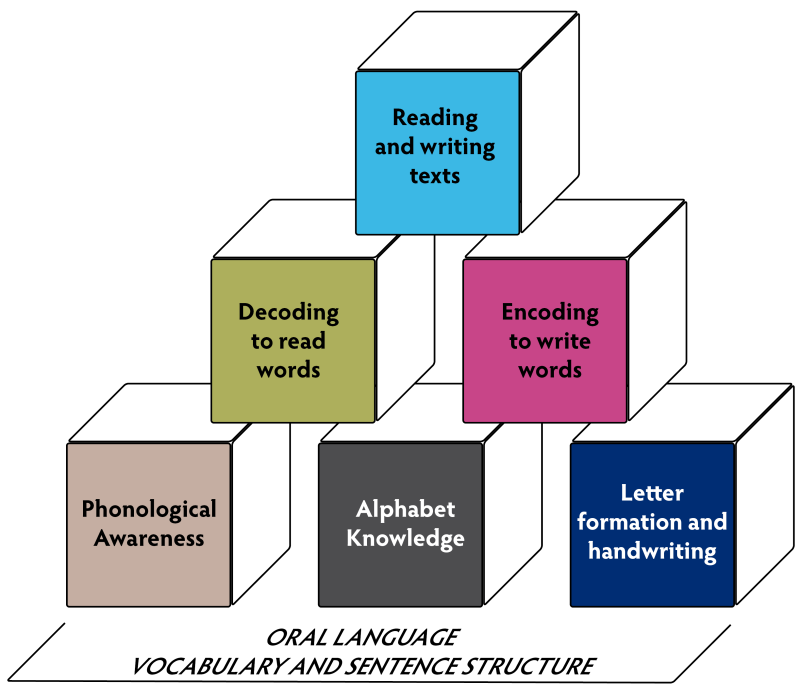

Research in reading acquisition has demonstrated that reading is a skill that must be explicitly taught to young learners, differentiated from spoken language which can be learned naturally. For young children, literacy begins with spoken language and learning component sounds. Once a learner can hear component sounds of language — or phonemes — then the learner can be taught phonological decoding. This process is the basis of literacy, and learners can be supported to reading fluency through practise, so word recognition becomes automatic.

Once reading is automatised, cognitive space is freed for comprehension. Structured literacy is a teaching practice that aims to guide learners through this process, ensuring students reach high levels of reading fluency.1

The draft curriculum for primary students is out now, and draft content for Years 7 to 13 will be released in Term 4. Content for older students will also focus on similar structured literacy principles, though some of this content will be limited to students who require additional support to reach expected standards.

The government has signalled that teachers will be supported into these changes with professional development and learning resources. With new funding being poured into the English curriculum and PLD in the area, the hope is that every child can be supported to achieve at the appropriate curriculum level.

In a statement to School News, a Ministry of Education spokesperson said that the updated English learning area is “designed to ensure every student has access to high-quality knowledge, texts, and evidence-based teaching practices. “For students, the aim is to develop literacy skills, critical thinking, and a love for literature. For teachers, the curriculum offers clear guidelines and support to enhance teaching effectiveness and consistency across schools.”

The curriculum will include a teaching sequence for teachers designed to support planning and coherent progression for students. The Ministry of Education said that this structured curriculum will still allow for teachers to design engaging lessons which cater to their students’ strengths, needs, experiences and interests without placing undue burden on educators.

By supporting students to achieve in the English learning area, student engagement will improve as learners can “see themselves as successful,” the spokesperson continued.

Young learners will develop strong foundations to support further learning in other areas.

“By fostering these critical skills early on, we are setting our students up for a lifetime of success and a love for learning. When students have the necessary skills to understand and interact with the learning content, they are more likely to be engaged and motivated to learn.”

The new English learning area will also emphasise comprehension, with the structured literacy approach “intended to enhance the understanding of meaning”.

“Comprehension skills are built both through texts read to students and texts students read themselves. Teaching advice includes focusing on meaning-making with every text. By building a strong foundation in literacy skills, students will be better equipped to comprehend and analyse texts.”

The curriculum aims to comprehensively address all areas of literacy, including oral language skills which are the foundation for reading and writing. The Ministry of Education states that oral language is a “crucial part” of the updated curriculum.

“Oral language activities promote collaborative learning and build confidence in public speaking and discussion, which are essential skills for academic and personal success.”

With the many changes coming into effect for Term 1 of 2025, schools and educators may find the scale of change and upskilling daunting. However, there are many programmes and resources available for teachers to transition toward the new structured literacy curriculum and address diverse abilities and levels within the classroom.

PLD has already been made available for structured literacy approaches and Rangatanga Reo ā-Tā in Years 0 to 3. This support will become available to Year 4 to 6 teachers in 2025.

Perspectives from literacy education professionals

The team from ITECNZ said indicators of literacy difficulties include problems with decoding, poor reading fluency, weak comprehension, and writing challenges. “Students may avoid reading aloud, have a limited vocabulary, or show frustration with reading tasks. A lack of motivation to engage with reading can also suggest they are falling behind.

“To support these students, educators should adopt a structured literacy approach that is explicit, cumulative, and responsive to individual needs. Regular progress monitoring helps track improvement and adjust strategies as needed. Involving families in literacy activities at home can further support students’ progress,” ITECNZ said.

“Structured literacy formats are however generally aimed at the primary sector and take quite a bit of work to monitor and personalise learning. Implementing research-proven software can be part of a very effective teaching model. There is even software specifically designed to cover these foundational reading skills with Years 7 to 13.

“Digital programs with adaptive technology will personalise individual learning, focusing on specific areas such as phonemic awareness or comprehension to improve literacy development. They provide instant feedback and engaging activities to help keep students motivated to improve their literacy skills.”

Professor Gail Gillon (University of Canterbury) from Better Start Literacy Approach said children’s early literacy success is a powerful predictor of their later comprehensive literacy skills. “Structured literacy approaches are designed to provide systematic and explicit teaching instruction. These approaches provide children with optimal learning conditions to facilitate the cognitive-linguistic skills necessary to learn to read and write well.

“Structured literacy approaches should include a strong focus on developing children’s phonic, phoneme awareness, vocabulary, oral narrative and oral language comprehension skills in the early school years. These linguistic skills are necessary for children to decode written words accurately and efficiently, to spell words, and to compose and comprehend written text,” Professor Gillon said.

“It’s critical that structured literacy approaches and monitoring assessments are adapted to ensure all learners, including those with complex communication needs, can benefit from these teaching approaches.

“It is also important that we embed structured literacy approaches within strengths based and culturally responsive teaching practices. We know, for example, that factors in addition to children’s cognitive- linguistic skills facilitate learning success for our Māori and Pacific Learners and for culturally and linguistically diverse learners. Other influencing factors include teachers and school leaders fostering strong home-school partnerships, respecting and valuing children’s cultural identity and home languages, and engaging and motivating children’s interest in literacy through culturally relevant literacy activities.”

Carla McNeil from Learning Matters said: “Dyslexia has historically posed significant challenges to student learning alongside our teachers not being equipped with sufficient knowledge of how the brain learns to read. However, I am optimistic that the future of literacy instruction will change this trajectory.

“The inclusion of funded professional learning for school teachers and educators to build knowledge and understanding, coupled with the implementation of mandated structured literacy approaches from 2025, will be instrumental in ensuring that both diagnosed and undiagnosed students with dyslexia receive the support they require throughout their school journey, enabling them to access the curriculum more effectively and experience success.

“With the introduction of a new curriculum, phonics checks, and structured literacy methods, schools will be better equipped with enhanced identification measures, support, and guidance for assessment and teaching practices. As schools embrace decodable readers to support word recognition and reading fluency and continue to utilise rich texts to expand vocabulary and comprehension, we can anticipate a meaningful and equitable shift in New Zealand’s approach to addressing dyslexia.

“For parents, advocates, and educators, this is a moment to be both excited and vigilant, ensuring that evidence-based instruction makes a tangible difference in the lives of our dyslexic tamariki.”

Paul George from Wendy Pye Publishing said decodable texts are an essential element of a structured literacy approach to the teaching of reading and provide the tools children need to practise and apply their developing phonic knowledge. “To understand their value, we need to understand what exactly decodable texts are and how they fit into literacy instruction.

“Decodable texts are books written specifically to support and match the scope and sequence of a structured literacy approach. All good Scope and Sequences teach phonic skills systematically and cumulatively, starting with simple alphabetic code and then moving to complex code and then extended code,” Mr George said.

“At each stage of this sequence, children learn letter-sound correspondences or GPCs (grapheme-phoneme correspondences), and the decodable books at each stage only feature those sounds that the children have been explicitly taught. Because these books are phonetically controlled, the children can sound out (decode) every word featured in the book, so they do not have to guess words,” Mr George said.

“Decodable texts are the ‘magic ingredient’ that allow children to confidently and successfully read by applying the phonic knowledge they have mastered to that point.”

Greg Carroll from Tātai Aho Rau Core Education said learning to read and write is a fundamental equity issue. “We know that teacher | kaiako skills and experience make the biggest difference in literacy outcomes for learners, supported by quality professional learning programmes.

“Educators should look for a strong evidence-based approach to structured literacy learning. Programmes should be responsive, consider the needs of individual settings, and be designed to support understanding of how the brain learns to read and write. Deeply understanding how literacy learning occurs means content knowledge and pedagogy can be woven together around what to teach, how to apply it in individual contexts, and why.

“With the support of a facilitator, kaiako can be empowered to plan and implement a structured literacy programme that reflects the unique learning needs of ākonga.”

Dr Christine Braid from Tātai Angitu Massey University said literacy professional development needs to empower teachers with the knowledge and skills to enable children to be the best reader and writer they can be.

“Effective PLD keeps teachers informed and reflective, and helps teachers recognise practices they should teach and some that they should change.

“We can help children build their background knowledge, vocabulary, and comprehension skills using a wide range of texts. Teachers will read poems, books that are stories and books with factual information. Books can be linked to children’s lives but also take children beyond what they know,” Dr Braid said.

“Discussion about books we read to children is an important part of literacy teaching and learning. Children need texts they can learn to read with too. These will include controlled texts such as decodable texts and later levelled texts to step children into a wide range of authentic text.

“When there seems to be so much change, teachers need also to feel that not everything needs to change. Growing teachers’ knowledge and skills combined with on the spot reflection about learning makes a powerful combination. Teachers deserve to feel that they can trust what they know and do when they embrace the process of teaching.”

Ros Lugg from StepsWeb said one of the challenges teachers face is the wide range of literacy levels in a classroom. “Even at the new entrant stage there is considerable variation in reading readiness, and these gaps often widen over time. It’s not uncommon to encounter a four-to-six-year disparity in literacy levels within a class. Some students may be several years behind their peers, while others might be years ahead of their age group.

“This variation makes standard whole-class teaching less effective, and potentially detrimental to some learners. The traditional approach of ‘Here’s your spelling list; I’ll test you on Friday’ is inadequate in several respects. There is usually insufficient time to ensure students genuinely understand how to use those words, but more damagingly, it’s inevitably the wrong level for a significant proportion of the class — far too easy for some, but unachievable for others.

“While a structured literacy approach is clearly beneficial, it must accommodate the different levels within a class. The solution lies in innovative educational technology, which allows students to work at their own level and reduces the teacher’s burden.”

References

1Scarborough, H.S. 2001. Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory and practice. In S. Neuman & Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy. New York: Guilford Press.