New study finds teachers face excessive financial strain from unpaid placement

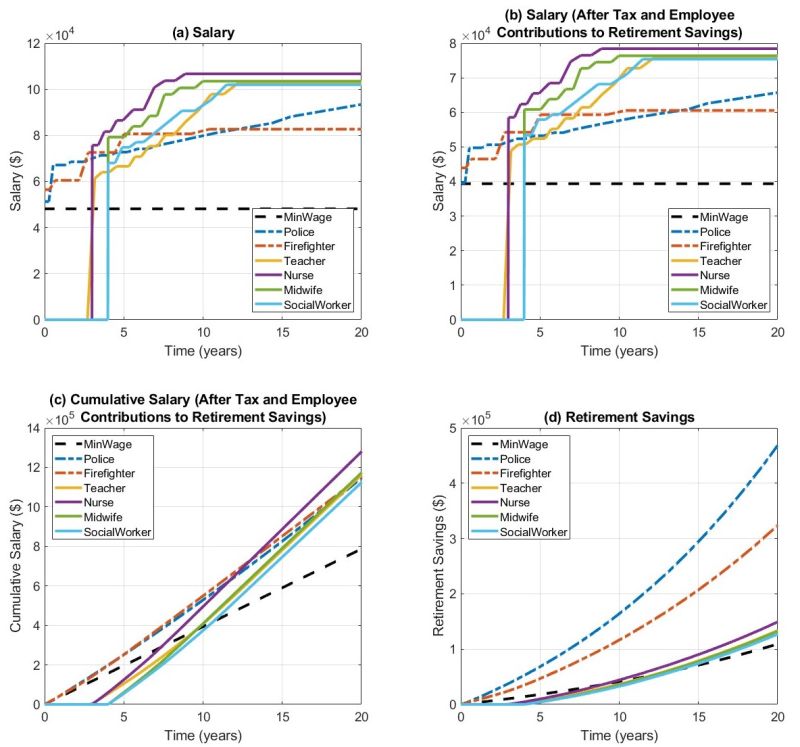

Teachers must work for almost a decade before they accrue more income than a minimum wage worker, finds new study.

A new study has uncovered the extent of financial hardships borne by trainee teachers and other professionals like nurses and social workers due to unpaid placements.

The study found that it takes 11 years since starting study for a teacher who completes a three-year Bachelor of Teaching to accumulate a higher aggregate income than a minimum wage worker for the same period. This figure includes course fees and living expenses. If an individual does not take out a loan for their three-year degree, it will still take them nine-and-a-half years to catch up to the earnings of a minimum wage worker.

Read the latest print edition of School News online HERE.

The authors concluded factors such as lost income and student loan repayments compound, and create long term financial effects that disadvantage workers who must take unpaid placements – not just during their training years, but long into their professional careers.

The study from the University of Canterbury was coauthored by Dr Leighton Watson, a senior lecturer of Mathematics and Statistics. He used a mathematical model to estimate the financial burden undertaken by professional trainees. Watson said he became interested in the subject as his wife is a primary school teacher, which brought his attention to the issue of unpaid placement work.

Watson said that he wanted to turn an economic lens on the negative impacts of unpaid placement, as “policy decisions are not driven by sentiment, but more driven by numbers… and I think the numbers are quite staggering.”

The study also estimated that a teacher would have to work nine years after graduating to accumulate more in retirement savings than someone who worked a minimum wage job.

Crucially, Watson says these estimates “are massively conservative”.

He points out that the mathematical model necessarily makes a number of assumptions and eliminates complicating factors. For instance, it doesn’t account for financial costs of taking time off or having dependents.

The model also assumes the control group to be a minimum wage worker who stays in their minimum wage job indefinitely. Anecdotally, it doesn’t seem to be the case that minimum wage workers stay in those jobs for their whole careers. Often, workers will receive promotions to higher-paid positions.

“In that case, the teachers are never, ever going to catch up.”

Watson points out the “important observation” that many of these professions are female dominated, whereas professions with paid training – police officers, firefighters, for example – are predominantly male-dominated.

“Even if a teacher doesn’t borrow any money or pay any course fees, it still takes them about 19 years before they cumulatively make more money than a police officer despite having a higher salary. The question is then: are we valuing police officers more than teachers? And the numbers here seem to argue that.”

Watson’s coauthor is Bex Howells, who is the campaign lead at Paid Placements Aotearoa. The organisation has been campaigning for paid placements in these professions. A bill is currently being considered before select committee.

Paid placements are not a novel idea. In Australia, the Commonwealth Prac Payment was announced last year to help support students in nursing, teaching and social work placements. The Australian Government has invested $427.4 million over four years to support students in these professions to ease cost-of-living pressures.

From July this year, eligible students undertaking a mandatory placement can access AUD319.50 per week to help cover costs during their placement.

In their factsheet on the payment, the Australian Government states it is an “invest[ment] in critical workforces”.

In New Zealand, teachers and healthcare workers were paid during training under an old model. Police, firefighters, customs and corrections staff are currently paid during training.

Is financial strain exacerbating teaching shortage?

Last Friday, the Teacher Demand and Supply Planning Projection by the Ministry of Education published its findings that schools could be short 1250 teachers in the near future. These shortages would be driven by immigration pressures on school rolls and the requirements for classroom release time.

In their paper, Watson and Howell suggest that the “financial sacrifice” of a professional degree like teaching is creating a barrier to entry and exacerbating the worker shortage.

“New Zealand and other countries using this same educational model are struggling to train and retain people in these skilled professions. This exacerbates existing diversity issues in the workforce as the financial sacrifice is even more challenging for those with dependents, existing financial commitments, or a lack of family support,” states the paper.

“The financial strain can be a significant deterrent for many.”

President of PPTA Te Wehengarua Chris Abercrombie agreed the financial burden of training was likely to deter teaching candidates, worsening the shortage.

“A significant number of university graduates simply cannot afford, or are not prepared to sacrifice, a year of unpaid initial teacher education. So unpaid placements deter many graduates and potential career-change teachers from even considering secondary teaching as an option. Some are forced to leave part way through the training as they cannot afford it.

“Most students need enough to cover their living costs, travel expenses, course related costs, and lost income on placement. In other words, they need to be paid for the work that by its nature excludes them from doing other paid work during that period and has a major impact on their lifetime earnings.

“Making teaching salaries attractive and removing the barrier of unpaid placements would have a positive effect on attracting more graduates into secondary teaching, which we sorely need, given the current worsening shortage.”