Inclusivity in education has been a focus in recent years, as we grapple with how the education system can perpetuate inequity.

Failing to account for neurodivergence is one example of how our education system can lead to inequitable outcomes. As the new English curriculum comes into effect this year, many kaiako will be wondering how we can support our dyslexic and other neurodivergent ākonga through these changes.

Read the latest print edition of School News online HERE.

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a neurodiversity, and a learning difference, where individuals process information through the “visual” centre of the brain. This means dyslexic individuals must convert written or spoken information into a visual format to understand. To respond, they must convert that visual information back into a written or spoken form. This process asks extra mental effort and time from dyslexic individuals, and they may appear to struggle with processing and producing written and verbal tasks in the classroom.

Dyslexia is estimated to affect 10 percent of New Zealanders.

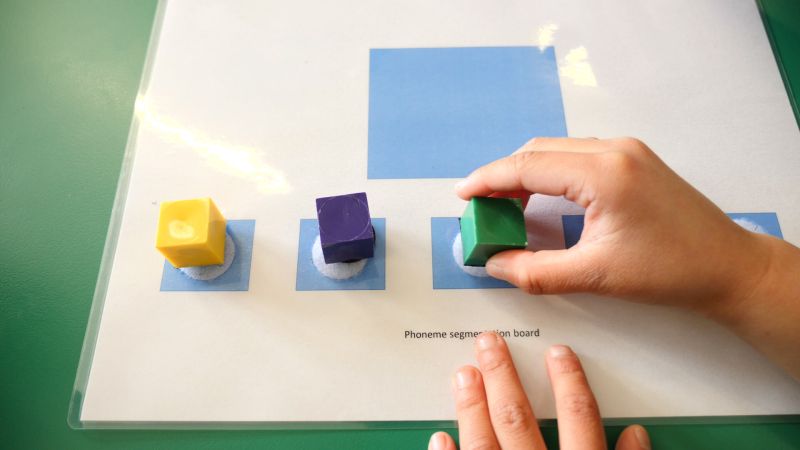

Children who are dyslexic may display poor phonological awareness. Older children may be able to answer questions well but struggle to write down their ideas.

Diagnosing dyslexia

Achieving a diagnosis for dyslexia can be complicated, time consuming and expensive, but ultimately life changing for some people with the learning difference.

Screening tests and interventions may be required for some students with dyslexia-like learning differences. An official diagnosis can only be provided by a registered psychologist or Level C assessor with the Lucid Rapid Test commonly used. For more on accessing screening or a diagnosis for dyslexia, teachers should consult available RTLBs and SENCOs. Information on assessment providers can be found on the website of Dyslexia Foundation of New Zealand (DFNZ).

Changes to English Learning Area

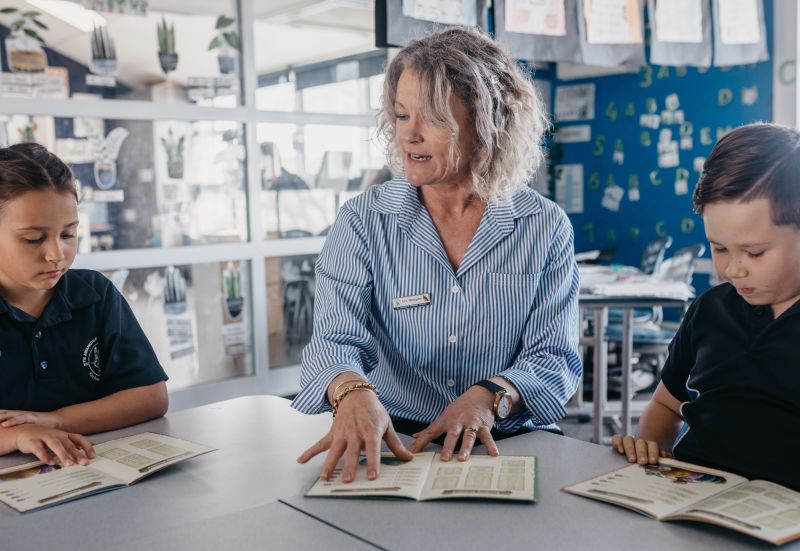

Explicit teaching and structured literacy have been shown to be effective interventions for children with dyslexia. This method has been written into the updated English learning area and teachers are guided through each step of literacy acquisition for Years 0 to 6.

This commitment to structured literacy approaches also extends to accelerative learning supports and resources for students who may need extra support. Additional support for learners will be accessed through annual staffing allocations from 2025. The Ministry of Education has also indicated that additional, targeted support for structured literacy will continue being developed and rolled out in consultation with the teaching community.

It is hoped this scaffolding will enable all students to acquire reading skills at appropriate rates. However, difficulty reading is only one symptom of dyslexia, and a change in approach to teaching reading only addresses one aspect of learning with dyslexia. So, what are some other measures teachers can take to support students with dyslexia in the classroom?

Supporting students with dyslexia

DFNZ promotes a “notice and adjust” model for supporting students with dyslexia in the classroom. The model is based on making simple changes to teaching and learning that can help students with dyslexia access learning. This can mean anything from changing the seating layout, to adjustment of noise levels, to using new technologies.

Teachers may modify lesson plans, breaking them into smaller chunks; adjust teaching style; minimise board copying and diction; allow extra thinking time; and/or use creative and multisensory approaches to thinking and learning.

Using technology may also help students with dyslexia in the classroom. Teachers may investigate using “dyslexic fonts”, designed to be more readable for people with dyslexia. Note taking software or using speech synthesis can also be effective supports.

Kaiako interested in learning more about supporting students with dyslexia can access PLD through the Ministry of Education, including support for implementing structured literacy methods. Questions to support schools with selecting appropriate programmes can be found on the TKI website.

What the experts say

Early identification of dyslexia is critical for effective intervention, said Carla McNeil of Learning MATTERS.

“Teachers should observe key indicators, including persistent difficulty with phonemic awareness and letter-sound correspondences. Other signs include inconsistent spelling, slow reading fluency, and challenges with sequencing or following multi-step instructions.

“How we teach is crucial to ensuring success for all learners. Explicit instruction provides clarity, structure, and opportunities for mastery. Active participation—through guided practice, frequent feedback, and opportunities to respond—builds both confidence and competence. Decodable texts help develop accurate and automatic word recognition, allowing students to apply skills systematically.

“For comprehension, students need exposure to rich, meaningful texts that inspire deep reading and critical thinking. Drawing on insights from Dr Maryanne Wolf, fostering a “reading brain” balances skill-building with engaging students in texts that promote empathy, creativity, and connection. Evidence-based teaching ensures equitable opportunities for dyslexic learners to thrive with confidence.”

Professor Gail Gillion, co-founder of the Better Start Literacy Approach (BSLA), and Professor John Everatt (professor in dyslexia), both from the University of Canterbury, note that even a short period of struggling to read can have adverse outcomes for learners.

“We strongly advocate that all children’s phonic, phoneme awareness and word decoding skills are monitored in their first year of formal reading instruction. Children who are not responding in the expected manner to evidence based explicit teaching in reading should be identified.

“For younger learners, effective intervention methods include explicit teaching in phoneme awareness, phonics word decoding, spelling, word recognition and building reading fluency. Interventions should also support meaning development.

“For older children with dyslexia, effective interventions incorporate more meaning-focused skills. This focus should be in addition to explicit instruction to advance their phonological and morphological processing skills. Older learners need to develop both speed and accuracy in recognising words in print. They also need to develop other cognitive skills that support reading comprehension and writing processes.

“It is important that all interventions to support children with dyslexia embrace strengths-based and culturally responsive teaching practices. Such practices can support children’s motivation and interest in reading and reward the intense effort that learners with dyslexia must exert to become proficient readers and writers.”

Ros Lugg from StepsWeb said that effective support in the classroom is crucial to keep students engaged and motivated.

“We know that many dyslexic students will have difficulties with the literacy aspects, but there are other areas teachers may not be so aware of. These include: remembering and following verbal instructions; organising themselves; planning their work; number skills; and concentrating for longer periods.

“As well as providing a structured and progressive literacy approach, teachers need to allow dyslexic and other struggling learners to progress at their own pace. A whole-class spelling test, for example, is often just setting these students up for failure. It’s important to provide a differentiated approach, which enables them to progress at their own level and achieve success.”

Ms Lugg notes that teachers should never ask a dyslexic student to read aloud in front of others. Teachers should also consider peer support strategies, using tools or reference materials like the ACE Spelling Dictionary, encourage students to ask for instructions to be repeated, and provide a checklist of tasks.

“And crucially, of course, be aware of individual differences and needs. No two dyslexics are exactly the same!”

The team at ITECNZ said learning differences and difficulties can be identified using appropriate assessment tools. “Early signs could include delayed speech, struggles with phonological awareness, slow reading, letter confusion, poor spelling, and difficulties with sequences.”

ITECNZ notes strategies such as multisensory learning, assistive technology for reading and writing, providing extra time for tasks, visual aids, and encouraging peer support are all effective interventions for helping students.

“Research has shown that as much as 90 percent of learners need at least some explicit instruction to become fluent readers and writers. A structured literacy approach is best, starting with systematic and explicit teaching of phonemic awareness, phonics, decoding and spelling.

“Digital reading programmes with a structured literacy approach can be beneficial to help teachers cater to the varying needs across a class. Prioritise programmes that personalise instruction for each student, and are research- or evidence-proven, not just research-based.”